Several weeks ago, I took my family to the filming of a TV program. As with most of this things there is a person who “warms up” the audience and which seems to involve the throwing of lots of lollies and sweets. (If only weddings used sweets instead of bouquets there might be more takers) The warm up act will always make one of two references to “having someone’s eye out with that one” as they throw the sweets.

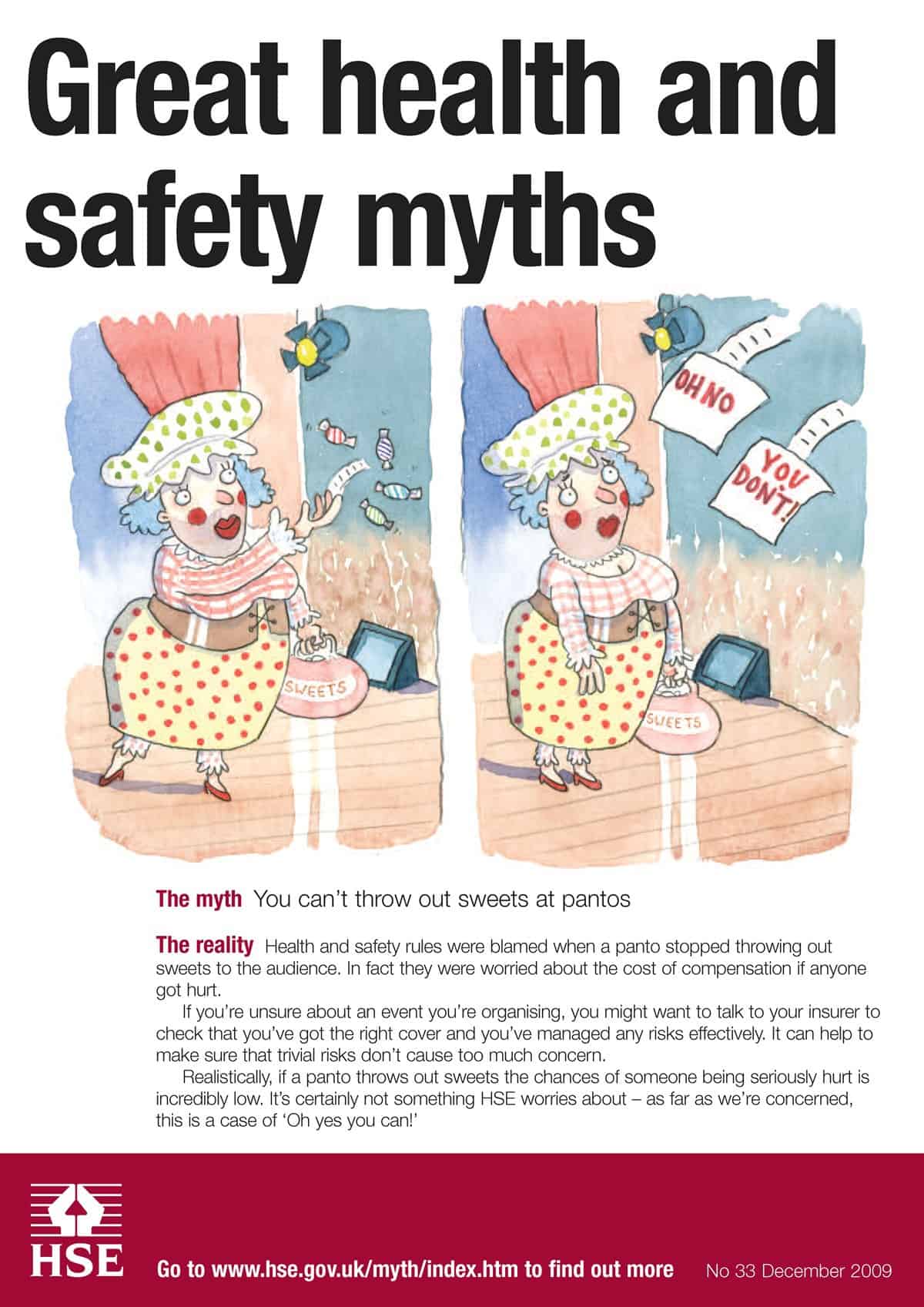

England’s Health and Safety Executive have chosen this “hazard” as their December OHS myth. It’s particularly important for the English as the pantomime season begins. The HSE says

England’s Health and Safety Executive have chosen this “hazard” as their December OHS myth. It’s particularly important for the English as the pantomime season begins. The HSE says

“Health and safety rules were blamed when a panto stopped throwing out sweets to the audience. In fact they were worried about the cost of compensation if anyone got hurt….

Realistically, if a panto throws out sweets the chances of someone being seriously hurt is incredibly low. It’s certainly not something HSE worries about …”

The hazard of being injured from stage projectiles is real and it was only 2000 when a law suit was settled between Dame Edna Everage and a man who was hit in the eye with a gladioli thrown from stage.

Whether being injured by a projectile from the stage is an OHS matter or a public liability situation is debatable. My risk management lecturer used to say that one should always sue the deepest pockets.

It is not OHS which is generating the safety rules. OHS regulators are reacting to the increased litigation that is being touted by lawyers, bled into the Western culture through US television programs and being seen as a “nice little earner” by some in the community. Most of the critics are facing the wrong target but are doing so because the OHS regulator is an easier target.

As an OHS professional, I would have to say do not throw anything into an audience or crowd unless it is an essential element of the performance. There are other ways of distributing treats.