The Cochrane Library has long been a good source of research information. Recently, the library undertook reviews of some of the seasonal influenza intervention and have produced a short podcast on the research.

Also, the Library looked at noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). The importance of this condition is high due to the damage being irreparable. In some countries, regular occupational hearing tests are a regulatory requirement in some industries and the research review did find some low-level research that supported hazard control through legislation. The review says

“There is contradictory evidence on the effectiveness of hearing protection and hearing loss prevention programmes. Higher quality prevention programmes and better implementation of legislation are needed.”

There was some support for the efficacy of PPE but training in the proper use of earplugs increased the benefits considerably. Those readers who are in the mining industry may find the NIHL podcast particularly useful.

These reviews are of rsearch studies and are not research in themselves, but they are useful summaries of a current state of knowledge on particular matters. Always look to the original data source if you wish to initiate prevention strategies or, better yet, contact you local OHS regulator and apply for a research grant so that you can generate research that meets the OHS needs of your industry.

In a similar way it is important that OHS professionals in industrialised nations with online references immediately to hand, and assistance at the end of a mobile phone call, realise that workplace safety can implemented, taught and regulated with a lot less. Some countries have no option but to work with lean resources but good skills.

In a similar way it is important that OHS professionals in industrialised nations with online references immediately to hand, and assistance at the end of a mobile phone call, realise that workplace safety can implemented, taught and regulated with a lot less. Some countries have no option but to work with lean resources but good skills.

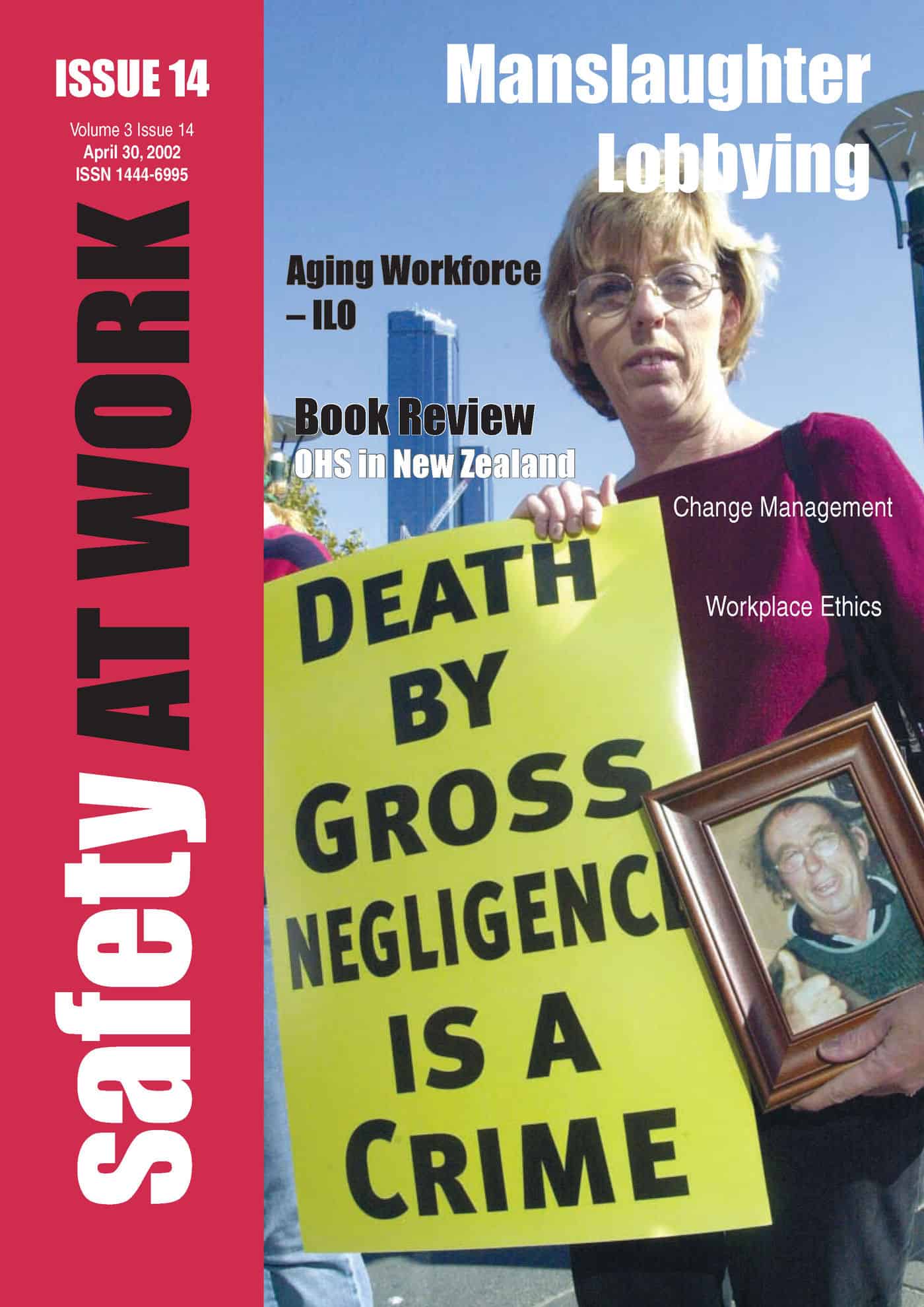

The policy has been allowed to fade from the books of most of the Australian left-wing parties but for a while, corporate manslaughter was THE issue. In fact over the last 10 years, it has been the only time that directors and CEOs from thousands of companies have paid serious attention to safety management.

The policy has been allowed to fade from the books of most of the Australian left-wing parties but for a while, corporate manslaughter was THE issue. In fact over the last 10 years, it has been the only time that directors and CEOs from thousands of companies have paid serious attention to safety management.