For many years SafetyAtWorkBlog and its forerunner Safety At Work magazine reported on various tragic fires in crowded nightclubs around the world. Several in recent memory include the 2003 Rhode Island fire that killed 100 patrons and for which, according to an Associated Press report from the time,

“Superior Court Judge Francis Darigan Jr sentenced 29-year-old Daniel Biechele to 15 years, but suspended 11 years of that sentence, and also ordered three years of probation.”

A brief report on the Rhode Island fire is in the OSHA media archives.

In March 2006, Safety At Work included an AFP report saying

“The municipal council has impeached Buenos Aires Mayor Anibal Ibarra after finding him guilty of dereliction of duty following a December 30, 2004 nightclub fire that killed 194 people.”

An earlier report on the mayor’s response is include at the CrowdSafe website.

Engineering and design company ARUP have provided SafetyAtWorkBlog with an article that analyses recurring elements of nightclub fires using the Santika fire in Bangkok from 1 January 2009 as a most recent incident. Below is the introduction to the article which can be found in full in the pages listed above.

Our thanks to ARUP for the terrific article.

LEARNING LESSONS FROM THE SANTIKA NIGHTCLUB FIRE

by Dr Marianne Foley and Travis Stirling, Arup Fire, Sydney

In the early hours of New Years Day 2009, fire engulfed Bangkok’s Santika nightclub, killing 64 people and injuring more than 200. Our knowledge of the events of that night is based on media reports and publicly available information, and the precise cause of the fire is still unclear. However, we do know that there are strong correlations between this and many similar tragedies at entertainment venues dating back as far as the first half of the twentieth century. While we wait for the results of the official investigation and coronial enquiries, it’s timely to ask questions about these fires. Why do they happen over and over again? Why do so many people lose their lives? What lessons can be learnt? And what practical measures can be implemented to stop them happening?

RECURRING MISTAKES

Arup’s analysis of case studies has revealed six themes that commonly contribute to the severity of high-fatality nightclub fires: insufficient exits, the presence of highly flammable materials, a lack of good fire safety systems, confusing environments, pyrotechnics and open flames, and buildings used inappropriately and maintained poorly. By addressing each of these themes, we aim to provide design solutions that could mitigate the risk of future nightclub disasters.

[The themes in the full article are

- Insufficient exits

- Highly flammable materials

- Fire safety systems

- Confusing environments

- Pyrotechnics and open flames

- Buildings used inappropriately or maintained poorly]

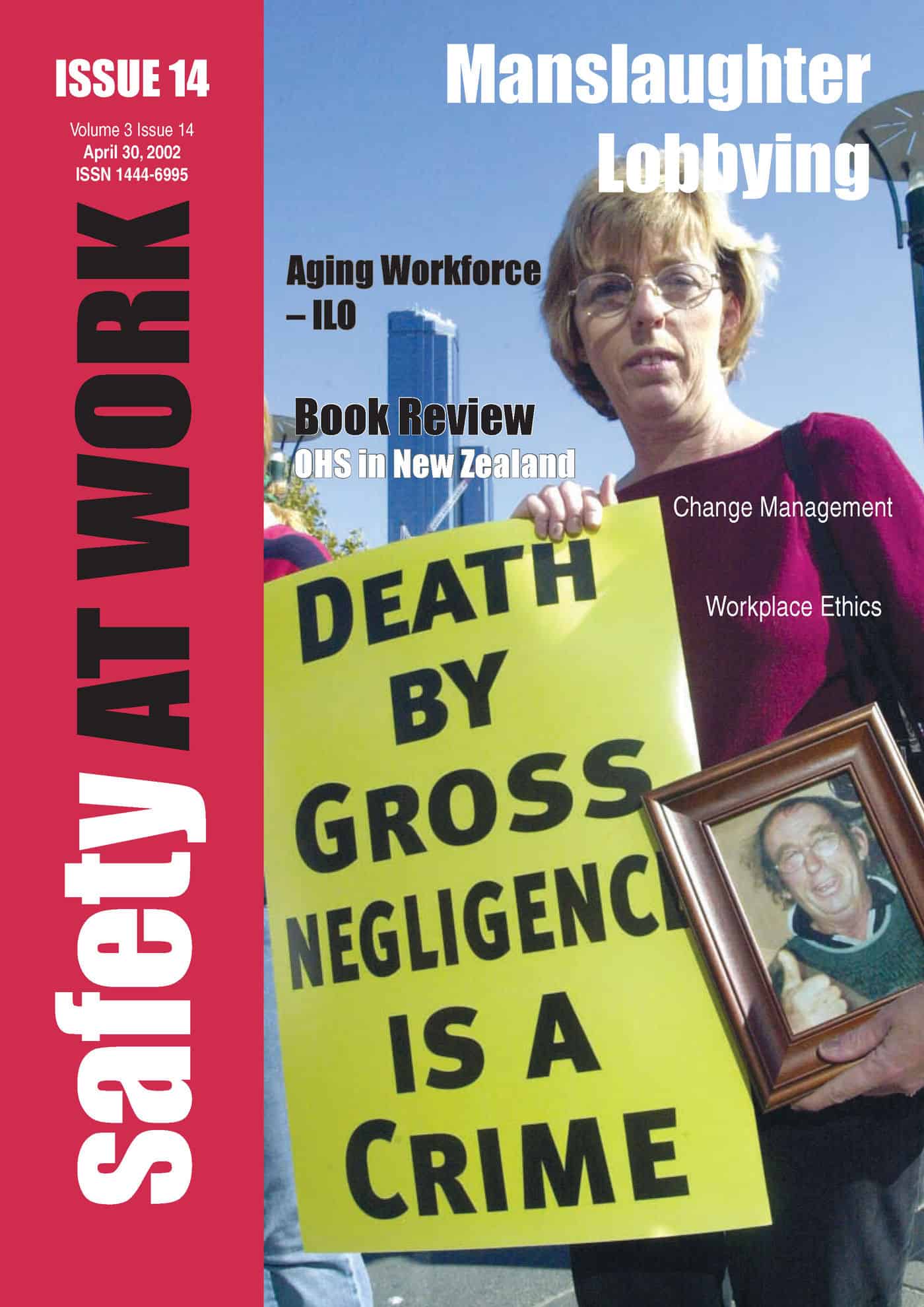

The policy has been allowed to fade from the books of most of the Australian left-wing parties but for a while, corporate manslaughter was THE issue. In fact over the last 10 years, it has been the only time that directors and CEOs from thousands of companies have paid serious attention to safety management.

The policy has been allowed to fade from the books of most of the Australian left-wing parties but for a while, corporate manslaughter was THE issue. In fact over the last 10 years, it has been the only time that directors and CEOs from thousands of companies have paid serious attention to safety management.