The Australian Financial Review on 24 March 2010 includes an article (only available through subscription or hard copy purchase) that states that the “tangle of state laws hampers compliance” by business on the issue of workplace bullying. Harvard Business Review reports on how to cut through the distractions and attend to a root cause of workplace bullying. Continue reading “Workplace bullying needs harmony and good managers”

Category: business

OHS awards consider work/life balance but not vice versa

On 15 March 2010, the Australian Government congratulated the winners of, and participants in, the 2009–10 National Work–Life Balance Awards.

According to a media release from the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations:

“The Awards…. recognise family friendly practices like flexible working hours, options for working from home, paid parental leave, job sharing, onsite carer’s facilities and study assistance.”

“No direct OHS performance indicators were included in the judging criteria for the 2009-10 National Work-LIfe Balance Awards.” Continue reading “OHS awards consider work/life balance but not vice versa”

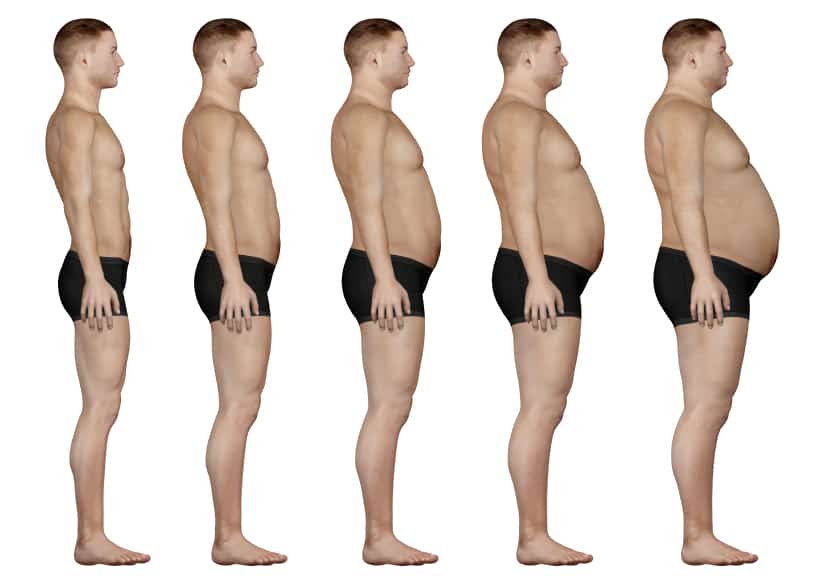

Does being fat equate to being unsafe at work?

There are several initiatives throughout the world under the banner of workplace health that have little relation to work. They are public health initiatives administered through the workplace with, often, a cursory reference to the health benefits also having a productivity benefit.

So is a fat worker less safe than a thin worker? Such a general question cannot be answered but it illustrates an assumption that is underpinning many of the workplace health initiatives. There is little doubt that workers with chronic health conditions take more leave but, in most circumstances, this leave is already accounted for in the business plan.

So is a fat worker less safe than a thin worker? Such a general question cannot be answered but it illustrates an assumption that is underpinning many of the workplace health initiatives. There is little doubt that workers with chronic health conditions take more leave but, in most circumstances, this leave is already accounted for in the business plan.

Sick leave is estimated at a certain level for all workers across a workplace and, sometimes, a nation. There is an entitlement for a certain amount of sick leave for all workers, fat and thin, “healthy” or “unhealthy”. It certainly does not mean that the entitlement will be taken every year but the capacity is there and businesses accommodate this in their planning and costs.

Remove this generic entitlement so that only working hours remain. Is a fat worker less productive than a thin worker? Is a worker without any ailments more productive than a person with a chronic ailment? Is a smoker more productive than a non-smoker or a diabetic or a paraplegic? Continue reading “Does being fat equate to being unsafe at work?”

Prominent OHS lawyer to facilitate workers’ compensation reform discussions

SafetyAtWorkBlog has been able to confirm the rumour that Barry Sherriff, a prominent Australian OHS Lawyer who recently joined Norton Rose, has been contracted to facilitate a series of exclusive forums on the reform of Australia’s workers’ compensation system.

Sherriff was one of the triumvirate who investigated a model OHS law for the Australian Government and should fulfill his contracted role for Safe Work Australia (SWA) admirably. Continue reading “Prominent OHS lawyer to facilitate workers’ compensation reform discussions”

LTIFRs (sort of) gone from Australia Post

The Communications Division of the CEPU has been in negotiations with Australia Post for some time to establish a pathway to better industrial relations. On 18 March 2010 a memorandum of understanding (MOU) was signed between the two parties, committing both to progress.

Of direct OHS interest is the following paragraph in the media statement about the MOU:

“As a gesture of good faith the MOU contains commitments from all parties that will apply immediately:

- Australia Post will host a summit in April between senior executives including the Managing Director and senior CEPU representatives on the future challenges facing the business, the unions and their members; and

- The removal of Lost Time Injury Frequency Rate’s in bonus targets for managers.”

Whether OHS will be discussed at the summit is unknown but the removal of LTIFR is of significance to OHS professionals.

Continue reading “LTIFRs (sort of) gone from Australia Post”

The OHS profession in Australia needs a saviour. Has anyone got one spare?

In December 2009, SafetyAtWorkBlog reported the comments by the English Conservative leader, David Cameron, on some concerns he had about the direction of occupational health and safety in England and how the newspapers were reporting OHS.

On 15 March 2010, The Independent published an article by the CEO of the Institute of Occupational Safety & Health (IOSH), Rob Strange. [IOSH says it is a personal opinion piece] Strange’s article is not a rebuttal of Cameron’s speech but is an important statement in the dialogue, or debate, that must occur if workplace safety is ever going to be treated with respect.

Strange must deal with the notorious English tabloid press and some of his article shows that no matter what relationship one may wish to have with a journalist, there is no guarantee that the journalist or editor will run your perspective, argument or rebuttal. His struggle shows how important it is to establish a respectful relationship with the media producers. His example should be followed by safety professional associations elsewhere. Continue reading “The OHS profession in Australia needs a saviour. Has anyone got one spare?”

The fatal consequences of riding in the tray of a pick-up or ute

In 2007, Pedro Balading fell off the back of a utility vehicle while working in remote outback Australia and died. On 16 March 2010, the owner of the Wollogorang cattle station, Panoy P/L, was fined $A60,000 over the death.

According to one media report:

“Pedro Balading, a 35-year-old father of three, was a Manila piggeries supervisor who arrived at Wollogorang Station in early 2007 and found himself isolated, underpaid and performing menial jobs. He asked to go home but was told by his employer, Panoy Pty Ltd, and the labour hire firm that brought him from the Philippines to complete his two-year contract.”

Work Health Authority‘s executive director, Laurene Hull said in a media statement:

“The danger associated with travelling in the back of a moving utility, where the risk of falling from the moving vehicle can result in death or serious injury is common knowledge,” Ms Hull said. “Panoy Pty Ltd failed to take appropriate steps to ensure the hazard posed by travelling in the back of utilities was known to the workers and the risks appropriately managed.” Continue reading “The fatal consequences of riding in the tray of a pick-up or ute”