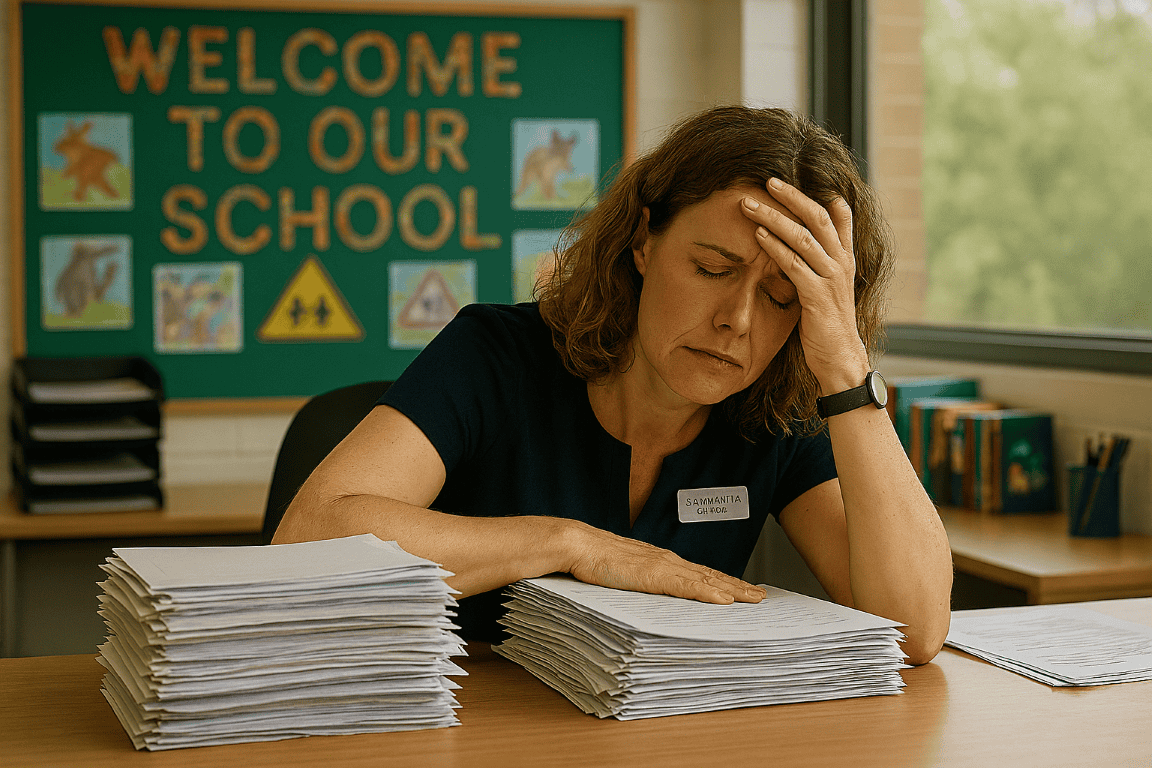

For the last few years in Australia, occupational health and safety (OHS) laws have required that the prevention of psychosocial hazards be given the same prominence as the prevention of physical hazards. The most effective recommendation for change is the redesign of work, but very few employers seem to be applying this control. Many employers are still asking (their Human Resources officer) what this psychosocial stuff is all about.

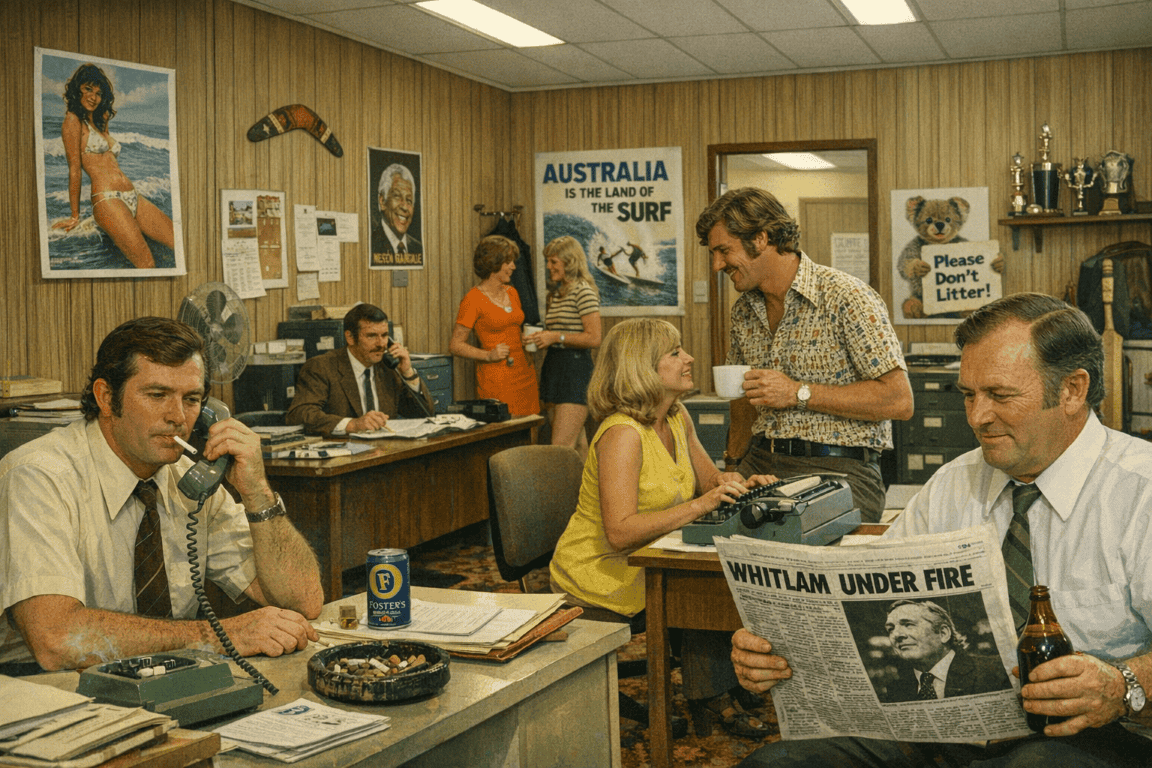

Examining organisational culture at one Australian institution that failed to prevent and may have generated psychological harm in the 1970s provides some context for contemporary OHS struggles.