There are several initiatives throughout the world under the banner of workplace health that have little relation to work. They are public health initiatives administered through the workplace with, often, a cursory reference to the health benefits also having a productivity benefit.

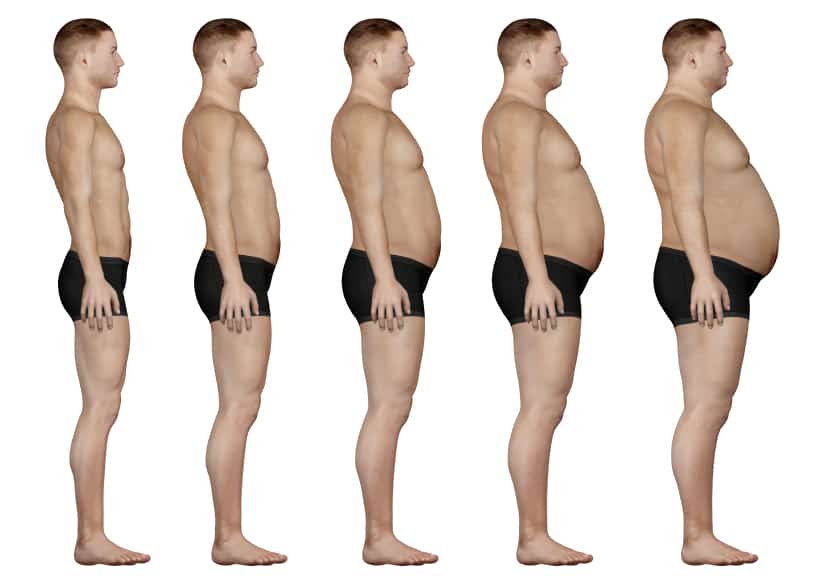

So is a fat worker less safe than a thin worker? Such a general question cannot be answered but it illustrates an assumption that is underpinning many of the workplace health initiatives. There is little doubt that workers with chronic health conditions take more leave but, in most circumstances, this leave is already accounted for in the business plan.

So is a fat worker less safe than a thin worker? Such a general question cannot be answered but it illustrates an assumption that is underpinning many of the workplace health initiatives. There is little doubt that workers with chronic health conditions take more leave but, in most circumstances, this leave is already accounted for in the business plan.

Sick leave is estimated at a certain level for all workers across a workplace and, sometimes, a nation. There is an entitlement for a certain amount of sick leave for all workers, fat and thin, “healthy” or “unhealthy”. It certainly does not mean that the entitlement will be taken every year but the capacity is there and businesses accommodate this in their planning and costs.

Remove this generic entitlement so that only working hours remain. Is a fat worker less productive than a thin worker? Is a worker without any ailments more productive than a person with a chronic ailment? Is a smoker more productive than a non-smoker or a diabetic or a paraplegic? Continue reading “Does being fat equate to being unsafe at work?”