On 13 July 2009, Tasmania’s Minister for Workplace Relation Lisa Singh braved

the elements to launch the Tasmanian Workers Commemorative Park in Launceston. The park is a work in progress and the local council is looking for support in the memorial’s completion.

According to the Minister’s media release, the Park was created to honour those who have died in the workplace.

“A memorial dedicated to those who lost their lives at work is an important way of reminding the community that workplaces can be dangerous places,” Ms Singh said. “The cost to the community can be calculated in dollar terms, but it is the social cost that is incalculable. How can anyone even imagine the grief felt by family and friends when a loved one is killed at work?”

It is not unreasonable to hope that every Workplace Relations Minister has talked with victims of workplace fatalities and illnesses and could “imagine the grief”. The Tasmanian government has pledged $A5,000 to the project.

Simon Cocker, Secretary of Unions Tas, told SafetyAtWorkBlog that the Tasmanian union movement is supportive of all memorials to injured workers and hoes that this is the first of a series of memorials in each of the major Tasmanian cities. The union movement is discussing how much financial support they can provide the memorial.

A media release from the Launceston City Council says:

Elizabeth Gardens, on the corner of Invermay Road and Forster Street, was chosen as the most appropriate site as it provides a peaceful and uncluttered spot suitable for contemplation and it has strong connections with past work places of Invermay. Its close proximity to the popular Aurora Stadium also gives the site state prominence.

The path through Elizabeth Gardens will be sealed and edged with bricks and an arbour will be constructed along the path, using materials selected for their relevance to a wide range of employment sectors.

The design includes a seating area that will be surrounded by ripples. The ripples will be made from clay bricks that represent the individuals who have died.

Cocker says that he hopes the memorial project (pictured below) can be completed in time for the International Workers Memorial Day on 28 April 2010.

In a similar way it is important that OHS professionals in industrialised nations with online references immediately to hand, and assistance at the end of a mobile phone call, realise that workplace safety can implemented, taught and regulated with a lot less. Some countries have no option but to work with lean resources but good skills.

In a similar way it is important that OHS professionals in industrialised nations with online references immediately to hand, and assistance at the end of a mobile phone call, realise that workplace safety can implemented, taught and regulated with a lot less. Some countries have no option but to work with lean resources but good skills.

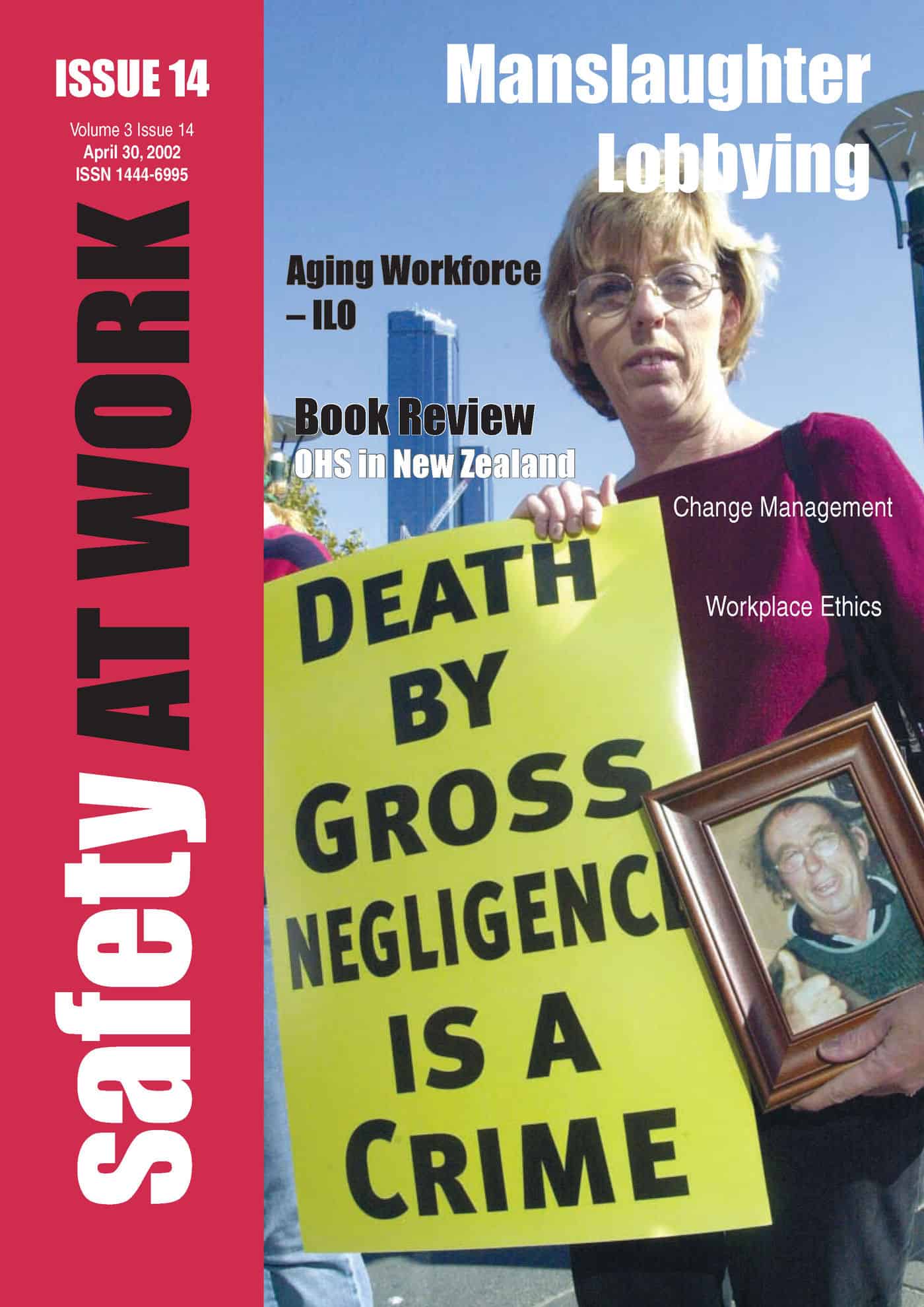

The policy has been allowed to fade from the books of most of the Australian left-wing parties but for a while, corporate manslaughter was THE issue. In fact over the last 10 years, it has been the only time that directors and CEOs from thousands of companies have paid serious attention to safety management.

The policy has been allowed to fade from the books of most of the Australian left-wing parties but for a while, corporate manslaughter was THE issue. In fact over the last 10 years, it has been the only time that directors and CEOs from thousands of companies have paid serious attention to safety management.