Barry Naismith‘s third report into the operations and performance of WorkSafe Victoria was released on July 22, 2014. Naismith produces these reports through a combination of publicly available information in the press, a dive into the resources of the WorkSafe Library (visit before it moves to Geelong) and requests to WorkSafe. This level of analysis and interpretation is rarely available outside of formal academic research and Naismith provides the all-important social and political context from which much academic occupational health and safety (OHS) research shies.

Barry Naismith‘s third report into the operations and performance of WorkSafe Victoria was released on July 22, 2014. Naismith produces these reports through a combination of publicly available information in the press, a dive into the resources of the WorkSafe Library (visit before it moves to Geelong) and requests to WorkSafe. This level of analysis and interpretation is rarely available outside of formal academic research and Naismith provides the all-important social and political context from which much academic occupational health and safety (OHS) research shies.

His latest paper focuses on 2015.

Naismith acknowledges that the rate of fatalities and workplace injuries continue to decline but also acknowledges that work-related injuries are underestimated and some areas of work, such as traffic accidents while at work, are ignored.

Politics

Most OHS professionals were baffled by the decision of the (then) Liberal Government to ditch the WorkSafe brand. Naismith quotes the incoming (Labor) Minister, Robin Scott:

“It made no sense to tear up the proud name of a world-renowned organisation that’s helped save so many lives.” (page 4)

Naismith wonders how much the short-lived exercise cost and implies that, without an adequate explanation but with budget cuts, the implication is that the move was ideological. If this was the case, the political advantage was fragile. The Liberal Party is perceived as the party of big business where Labor is of the workers, political donations records seem to support this. The Liberals had the chance, through not weakening WorkSafe, of regaining some political credibility with workers and of not losing credibility with the trade union movement. But the Government was rampant on its red-tape strategy even though WorkSafe was mentioned prominently in the red-tape rhetoric but was almost missing from the reality.

WorkSafe Victoria has been criticised in this blog for its poor media performance. The budget and staffing cuts go a long way to explaining this performance but Naismith provides evidence that in 2015 WorkSafe issued 76 media statements, 50 more than in the previous year (page 6), prior to the Labor Party regaining power. This type of communication, rarely covered in the mainstream press, gets an enormous run in the new social media. Every release is retweeted on Twitter and analysed on LinkedIn forums.

Mental Health

Mental health is mentioned several times in the paper. Naismith believes that although manual handling incidents still represent 50% of workers compensation claims, mental health claims are increasing. This increase is, as with many injuries and illnesses, under reported. Naismith explains the broader context:

“Generally employers have not been managing these increasing types of claims well and as a result many affected workers have been harmed and have not accessed the claims system for assistance. The cost therefore has been borne by individuals, the medical system (eg through Medicare) and the community (eg through Centrelink). The OHS and compensation system is by its very nature reactive and adversarial but improvement in prevention initiatives have been a hallmark of OHS in Victoria early in the century. However this is one area where the system has struggled in recent years and needs more focus.” (Page 8)

He seems to be on the path of measuring the total cost of injury, an important concept supported by Safe Work Australia that is not gaining the attention it deserves. If one looks beyond the billions and the GDP percentage to who pays the highest cost, there is a major question about how workplace safety risk is calculated.

He seems to be on the path of measuring the total cost of injury, an important concept supported by Safe Work Australia that is not gaining the attention it deserves. If one looks beyond the billions and the GDP percentage to who pays the highest cost, there is a major question about how workplace safety risk is calculated.

Two Systems – One Aim

The bifurcation of OHS into harm prevention and harm remediation is a cornerstone of WorkSafe Victoria. This situation is mirrored in the workplaces and runs counter to the whole-of-life process to which businesses operate. The end-users, the business owner, see OHS as a continuum from worker employment to worker departure but thew OHS and Human Resources professions do not play well together and workers compensation involves large insurance companies which adds an additional set of values and performance indicators.

Naismith writes:

“The safety and compensation systems managed by the VWA are meant to form part of a cohesive, integrated cycle of constant improvement and delivered under a seamless “two systems; one organisation” scheme. That’s the theory. The two systems have different cultures, mindsets and even incompatibilities – safety is about legal compliance and enforcement to address a criminal “wrong”; compensation is about determining insurance liability in a “no blame” environment and then redressing measureable “harm” and providing the required medical healing.” (page 16)

Naismith seems to believe that more can be done with the Victorian Workcover Authority (VWA) to harmonise these approaches but is critical of the rosy picture of Return-To-Work that WorkSafe currently promotes.

“The challenge of the future is how two parallel systems in one agency could work more closely on ever tightening the loop to improve safety performance, given limited resources, and what mechanisms or processes could be developed to make that happen. It is understandable that the claims system can result in confusion and even bitterness among claimants who do not understand why the employer hasn’t been prosecuted for breaking a safety law when they have admitted liability under compensation law. Ideally the employer should be genuinely remorseful and the aggrieved worker forgiving as appears to be the case in WorkSafe’s cheery RTW advertising images of 2015.” (page 16)

Naismith raises a crucial point about an injured worker’s perspective on the whole-of-life process. Workers usually share the business owner’s perspective but the social relation can change dramatically after an incident that may have been out of their control. Productive worker to rehabilitation nuisance. An integral member of a workplace to someone who is shunned by formerly close workmates, on legal advice. WorkSafe has a major challenge in explaining why a workers compensation system encourages this social confusion at a time when workers are psychologically struggling with how their lives have changed.

Deaths

Naismith is also critical of those who downplay the significance of workplace fatalities. He writes that the number of deaths is much more than “unacceptable”.

“It is worse than that – it is inexcusable and a tragic stain on the OHS system. The reason for such harsh words is that workers continue to be killed for the same reasons, simply because employers fail to implement the minimum known and acceptable level of safety for high risk tasks. It has been a similar pattern of tragedy since 1985 for the approx. 985 people and others who have died from largely preventable work-related causes.” (page 17)

This is a major OHS frustration and one that contributes to the cynicism that OHS professionals need to work hard to combat. Hazard control measures are well known. There are few hazards that have no controls at all, even mental health incidents have established control and prevention measures. The persistence of common workplace incidents indicates that there is a fundamental ethical problem in the way businesses are managed.

Just as workplace injury costs to business represent a comparably small part of the total cost of injury, so official workplace death figures exclude certain injury types. Naismith lists them:

- “death at work where the work-related cause is uncertain or where the deceased may been working alone

- deaths of those working on public roads eg hit by vehicle

- death from work-related vehicle crashes on public roads eg truck crash

- death at work from occupational violence or a criminal act

- death from traumatic illness eg heart attack

- death from a work-related suicide

- long onset death from occupational illness eg cancers as asbestos-related” (page 18)

Claims Costs

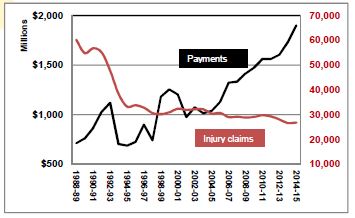

Claims costs continue to rise while claims numbers have dropped. Note: claims benefits have risen over the life of the scheme to provide fair level of benefits and are indexed. Source: VWA/interpreted by OHSIntros

Just as asbestos-related illnesses have identified the shortcomings of workers compensation systems (black lung may be the next of this type of injury), mental health claims are a similar challenge. Workers compensation systems were structured a long time ago to address traumatic sudden injuries, and they struggle to deal with illnesses that may manifest some time after exposure or injuries that are only visible psychologically.

Naismith also writes about an element of Workcover Injury Insurance – Death Claims. He points out that 985 work deaths were reported to WorkSafe since 1985 but that the Victorian Workcover Authority has paid out 4249 death claims! (page 21) A full payment is currently “$589,000 plus related pain and suffering” (page 21) and Naismith writes that

“Last financial year total cost for the 88 claims was $23,291,637, a similar figure to the previous financial year.” (page 21)

Such a figure is a further commodification of workers but for those political critics of OHS, and many remain, who understand safety only in dollar terms, the figures above and others in Naismith’s report provide an argument for improving OHS that is impossible to argue against.

Naismith uses a clarity of language that makes for an easy read of uneasy data and findings. He raises important questions that are usually backed by evidence that he has developed from VWA data. His background in WorkSafe Victoria offers a useful perspective that is not distracted by fads or buzzwords. Each of his reports share Naismith’s conversational tone but there is a noticeable maturity in the most recent report. This maturity does not mean that he is not angry and frustrated but he doesn’t need passion to make a point that data and interpretation can make so much better.

I recommend all of Barry Naismith’s reports to any reader in HR, OHS or Return-To-Work. They are terrific analyses undertaken just because they should be.