On November 12 2014, the Safety Institute of Australia (SIA) conducted its first large seminar on the certification of occupational health and safety (OHS) professionals. The seminar had an odd mix of some audience members who were suspicious, others who were enthusiastic and presenters who were a little wary. There were few who seemed to object to certification but, as the SIA admitted, the process is a long way from complete.

Justification for Certification

Certification works when it is either mandated by government, usually through legislation, or in response to a community/business/market need. Australia does not seem to have either. The SIA explained that there is a “legal requirement” for OHS certification by placing it as part of the OHS due diligence obligations of Australian businesses, that Safe Work Australia (SWA) sort-of refers to it it in its National OHS Strategy and that the “Recommendation 161” of an unspecified international law:

“….calls for organisations to have access to “sufficient and appropriate expertise” as a basic right of all workers.”

There is no such Recommendation but there is an Occupational Health Services Convention, 1985 (No. 161)

Convention concerning Occupational Health Services (Entry into force: 17 Feb 1988) – a International Labour Organisation Convention that Australia has not ratified.

The SWA strategy repeatedly mentions the important of “health and safety capabilities” as a “national Action Area”. It specifies this action area as:

- “Everyone in a workplace has the work health and safety capabilities they require.

- Those providing work health and safety education, training and advice have the appropriate capabilities.

- Inspectors and other staff of work health and safety regulators have the work health and safety capabilities to effectively perform their role.

- Work health and safety skills development is integrated effectively into relevant education and training programs.” (page 9)

In the strategy’s chapter on Health and Safety Capabilities, SWA says:

“In a decade many existing workplace hazards will still be present and new ones will have appeared. It is particularly important that education and training enable those who provide professional or practical advice to competently deal with old and new hazards. Those who provide advice need to know when to refer the matter to others with appropriate expertise.” (page 12)

There is no mention of certification in the SWA strategy but the SWA is sympathetic to certification.

It is significant to acknowledge that the issue of certified OHS professionals has existed for some time and that even after serious consideration by SWA’s predecessor, the National OHS Commission (NOHSC), a certification process was not recommended or implemented. The Guidance Note for the Development of Tertiary Level Courses for Professional Education in Occupational Health and Safety [NOHSC:23020 (1994)] states that a 1990 workshop discussed, amongst other matters, the “possibilities for improving the certification of occupational health and safety professionals” (page 2). No recommendations for certification resulted.

Chris Maxwell QC, in his review of the Victorian OHS Act, quotes a submission from the Victorian WorkCover Authority

“…. The VWA is aware that some OHS consultants have been sued for poor performance by those who have contracted them. This industry may benefit from some form of industry based accreditation scheme, similar to those operating in the accounting field, so that consumers can gain a level of confidence about the consultants that they may engage.” (271)

The SIA seemed to imply in its presentation that the emphasised quote above was by Maxwell himself and this is clearly not the case.

The SIA was deeply disappointed that the OHS harmonisation process in Australian failed to require, through legislation, the use of OHS advisers who were suitably qualified. The review body, in its second report

“…recommend[ed] that persons conducting a business or undertaking be required, where it is reasonably practicable to do so, to employ or engage a suitably qualified person to advise on health and safety matters. Details of the qualifications should be provided in regulations.” (page xxiv)

The second report referenced three influential business groups who submitted that

“There was concern that [the recommendation above] would restrict business freedom and innovation by focusing on workplace and business arrangements rather than on improving OHS outcomes. Another criticism was that mandating such appointments would increase red tape and costs for little benefit, provide for blame shifting and management delegation of responsibility, as well as reducing consultation and shared responsibility for OHS.” (page 225)

It is understood that the avoidance of delegating OHS responsibility was a particularly influential reason for not including a legislative requirement in the new Work Health and Safety laws.

However change does not come from governmental reports and reviews but from how a government responds to those reports. The Ministers’ responses to the harmonisation report are available here. Recommendation 139 (page 36) addresses the suitably qualified matter.

The Victorian WorkCover Authority’s (VWA) position on “suitably qualified” advisers was touched on at the seminar, showing some solidarity for SIA’s initiative. VWA’s position revolves around its 2008 guideline. It is a useful summary but Victoria is excluded from the Work Health and Safety laws that apply in most other Australian States. It has relinquished its leadership role in many areas of OHS and the national relevance of this guideline is minimal.

In a recent National Safety magazine article (not available online), Dr Robert Long, a longstanding critic of the SIA, said of the certification scheme that

“If the government wants to accredit safety professionals in legislation, then that is an entirely different issue, but this is a private organisation trying to set up a process of accreditation and draw people into it.”

For SIA’s certification process to succeed it will need to convince the business and industry associations, and many in the profession, that certification addresses all of the concerns listed above. Any industry uncertainty about the certification process could be severely damaging.

Competence

The SWA quote above, significantly, mentions competence, a word that was absent from the SIA presentation until SafetyAtWorkBlog raised it. The SIA’s certification process has as its motto or logo:

CAPABLE CREDIBLE CERTIFIED

The SIA responded that competency is part of a professional’s capability and left it there.

Competence is a commonly understood term in business, the training sector and the community meaning that a person is suitably qualified to undertake a specific task. Many companies verify competence through analysing a worker’s “certificates of competence” and, increasingly, requiring a practical demonstration (at least in the construction sector). The SIA’s proposed certification system is a verification of competence but the SIA again misses the opportunity to capitalise on an existing, common term preferring a, perhaps more accurate, term that requires explanation.

Terminology

One area that requires tidying up in the SIA presentations and information on this program is semantics. The speakers may have a clear understanding of the different terminologies but this was not communicated clearly to the audience. There were mentions of

- “safety professionals”,

- “safety practitioners”,

- “safety people”,

- “Generalist OHS professionals”

- “Generalist OHS practitioners”.

These terms were not only used in terms of certification levels but in general speech as synonyms. The SIA should settle on one term that describes the members of the safety profession AND this term should be one that is readily acceptable to the broader community, rather than trying to invent new terms. The term that most fits the needs of both the Institute and the community is “safety professional”. Whether this relates to ergonomists, hygienists or health and safety representatives should be irrelevant.

If the SIA wants to cut through the ignorance of what it and its members do, it needs to take ownership of the common terms for its profession and not impose layers of unnecessary explanation. Clarity and uniformity of terminology is essential if the certification process is to succeed.

SIA’s Certification Process

The SIA stated that certification achieves

- “certainty to consumers

- demonstration of due diligence by clients

- role recognition

- recognition of education, knowledge and experience,

- recognition of practitioner and professional roles

- international comparability.”

It can, but people will only trust certification if the process is independent, robust, transparent and fair. The process proposed by SIA seems to fit these criteria.

The SIA stated that the process will comply with the international standard ISO/IEC 17024:2013 – Conformity assessment – General requirements for bodies operating certification of persons (online purchase required). This is a strong position and one that should be promoted as part of any SIA promotional campaign. The standard should satisfy many of the SIA’s critics on matters of independence and transparency as it stipulates the management of impartiality, the criteria for examiners/assessors, confidentiality, and, most importantly, an appeals process, amongst other matters.

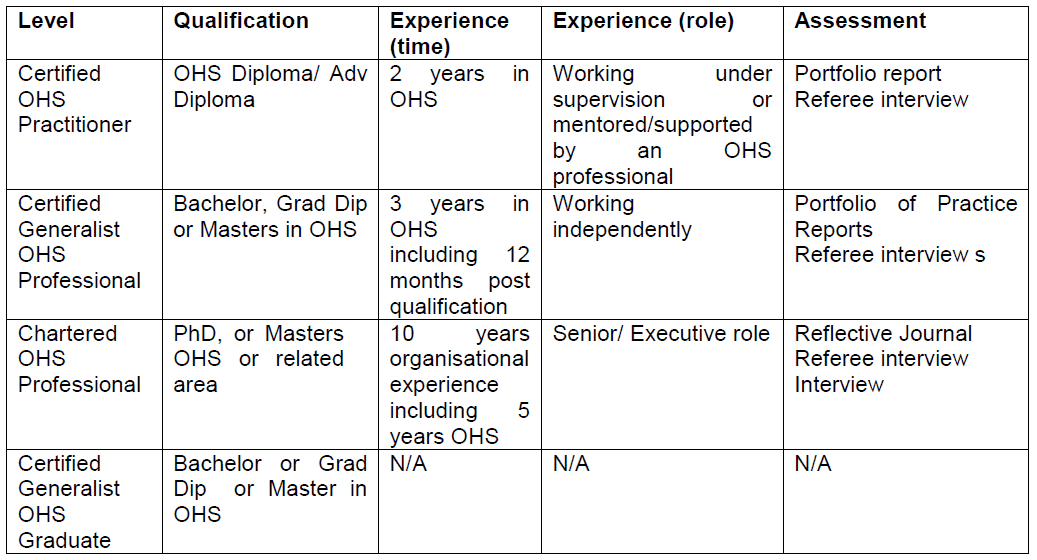

According to the SIA’s current information sheet there will be three categories of certification, not counting the Graduate level:

There was some debate on the content of these categories but there was no strong objection to the categories themselves.

Formal/tertiary education

The SIA’s university bias was on display in response to one question from the floor which resulted in the questioner walking out. The question was that not every safety professional may have the time, the resources or the capability of undertaking tertiary education. The SIA’s response was “Why Not?” This response showed a lack of understanding for some of its membership and its potential market, and the walk out was understandable.

On the issue of cost, the SIA response was that any course costs are fully tax deductible. This is a common response to issues of safety-related and education-related costs but ignores the fact that there may be a significant financial outlay that an individual or family needs to carry until tax time. When tertiary education is undertaken in Australia, it usually generates a debt that the government deducts from one’s pay after a certain income level is reached. It may not be possible for someone to take on such a debt, regardless of the amount.

Professional development usually involves a financial cost but few workers have a sympathetic employer who covers the education cost and/or provides study leave. In fact, another question from the audience reminded the SIA that those working in the small business sector may have even less capacity to undertake the necessary training to maintain or improve one’s safety qualifications.

Another question took considerable time for the SIA to understand. One audience member asked whether the SIA had any processes in place to assist people in beginning the tertiary education process. The simple answer was no, but the SIA later acknowledged that an entry/pathway/preparatory process was a good idea and should be seriously considered. This acknowledgement should be applauded but one could ask why such a basic process was not already included in the certification proposal. This lack illustrates the SIA’s tight focus on education through the university sector and a seeming lack of understanding of the vocational education sector, processes and role.

Early in its presentation the SIA stated that 60% of Safety Institute of Australia members have no formal OHS qualifications. This is a staggering figure for a professional organisation of over 60 years’ standing and makes the lack of understanding on vocational training even more stark. Surely, any organisation proposing a certification process would have included a pathway process if over half the membership had no formal qualification.

The bias of the SIA was also mentioned in a recent article in National Safety magazine (available only by subscription) where through certification:

“…diploma-qualified practitioners will be recognised as ‘practitioners” while university-educated ones will be recognised as “professionals”.”

The reason for this split between practitioners and professionals and for the use of the term “generalists” has never been fully explained and continues to expose the SIA to the accusations of elitism.

Money

One issue that was not discussed yesterday was money – the increased income stream possible from becoming a certified OHS professional. To satisfy due diligence requirements and expectations in any industry, companies want to obtain the best available advice, as far as is reasonably practicable. In relation to the certification table above, it is reasonable to expect that the higher the certification, the higher the hourly rate for OHS advice.

The SIA would be foolish to even hint at any relationship between certification rates and higher remuneration but one can guarantee the safety professionals are already talking about it. They will be assessing the rate of return on financial outlay and time allocation against the top level of certification. This relationship will be outed when the first professional indemnity insurers reduce premiums in relation to level of certification.

The Safety Institute of Australia must stay above the issue of remuneration but would be foolish not to be considering the potential financial benefits to its members.

Baggage

One of the biggest impediments for the introduction of its certification scheme is that the SIA’s reputation has yet to regain the prominence it achieved prior to a bitter internal row that involved legal action on defamation among other things. The SIA’s profile was not very high prior to the turmoil and its membership numbers seem to have hovered around 4000 – 5000 for well over a decade.

It is rebuilding and the actions of the new executive are promising however financial figures provided to members in late 2014 indicate that the SIA has run at a loss of over $200k for at least its second year in a row – a difficult position for a not-for-profit organisation and one that SafetyAtWorkBlog has been told is also a registered charity.

The Safety Institute of Australia should not be criticised for trying to introduce a certification scheme, as no one else in Australia is doing so. The need for such a scheme can be debated but if the gamble pays off, it could ensure relevance for the SIA for many years to come.

The VWA guideline from 2008 illustrated that at least one regulator was sufficiently concerned over the issue to provide some clarification in a position statement. Indications from Safe Work Australia is that it would support an industry-based certification scheme. But the certification gamble is risky and requires careful planning, broad consultation and serious negotiation with the broader industry and regulatory community – not the SIA’s traditional strengths.

Kevin, this is an important discussion, and should involve the SIA as well as a multitude of other interested stakeholders. However, the experience of other stakeholders tends to be one of alienation on behalf of the SIA.

I spoke with a representative of another high profile national safety association earlier this year, who mentioned that they had attempted to engage early with the SIA on this matter, but were blatantly ignored. They were informed by the SIA that as a commercial organisation they would not be included in consultation or collaboration in the development of a certification model given a perceived conflict of interest. I find this incredulous given that the SIA stands to benefit significantly by their proposed model.

Further, having posted my views in a range of LinkedIn groups on this subject, I have been contacted directly by a number of people who share Rob Long’s views of this toxic organisation. Some of these people had previously been members of the SIA (some at relatively high levels), and whilst there is some agreement that there is merit in a certification model, the approach taken by the SIA is far from inclusive and does nothing but further divide people.

Dean, I agree it is important and I hope my article has done justice to the issue.

I think the SIA has misjudged the strategy by focussing on the university sector. The SIA has always had a close relationship to several universities but this type of relationship is insufficient for a program that proposes to be industry-wide. If Safe Work Australia supports certification, on an industry basis, it may need to be concerned about the SIA proposal, particularly after reading many of the comments on this blog and elsewhere.

I don’t know which organisation you are referring to but in a recent National Safety article I think, as I don’t have the article with me, that Adam Baldock of the National Safety Council of Australia has said that the NSCA would support a certification scheme for OHS professionals, but I think he expressed reservations on the SIA proposal.

The accusation of a commercial conflict-of-interest is hard to understand as over the last few years the SIA has stated that it will be establishing a commercial arm to its organisation, one that provides OHS training and other services, thereby becoming a commercial entity. If it was to structure this commercial arm at great distance it would still be receiving some income, so is open to its own accusation. It would be up to the SIA to determine which is more important – the generation of income or the maintenance of its charity status for taxation purposes.

The argument is even sillier if one considers the relationships with universities that have become increasingly commercial over the last 20 years. Yes the Australian Government covers the cost of study under its student loan scheme but there is plenty of evidence of various Vice-Chancellors stating the reality of non-government funding.

The SIA MUST be inclusive in this certification scheme, even if it means that it would need to relinquish some of its control.

Your last point involves the SIA’s sullied reputation. It seems the further the OHS certification scheme is from the SIA, the better its chances of success.

Perhaps the best resolution to the issue is for the certification scheme to be established and administered on an obvious, transparent and strong commercial basis but that also has a strict independence from all of its constituent parts. As the concept of a just and fair culture is promoted to companies, it should also be applied in OHS certification – in structure, application and accountability.

Mick, thanks for your comment. Do you have any cost estimates for university OHS courses? It has been some time since I studied OHS at university and would say that I have learnt from “self-education” as much as I did in any university course. Most importantly, I learnt the shortcomings of university study.

I am a strong advocate of continuous learning while working through public seminars conducted by law firms and some universities, by attendance at affordable conferences and most usefully by allocating time to meet with my peers and to discuss safety.

I note that a feature of Rob Long’s tertiary courses is the encouragement for students to have regularly discussion groups that relate to the subject matter. Discussions may sometimes become heated but at least alternative perspectives are presented. One of the strongest contributors to poor advice and decisions is the lack of exposure to alternate viewpoints.

I agree that lecturers also need to be suitably qualified for their position but, sort of in relation to the previous paragraph, education or experience from outside the OHS discipline is vital to broadening the understanding of OHS to the contemporary culture. Some the leading thinkers on OHS In Australia are from sociology or psychology disciplines. My first tertiary qualification was in literature with a strong sociology theme. The industry experience is also vital; I would argue perhaps more vital than a PhD.

Hi Kevin;

With regard to cost, I’m doing the Grad Cert to Masters program with ACU. By the time its completed, cost will be around $27k.

Rob, I thought for a while before allowing your comment. I don’t agree that the SIA is currently as dysfunctional as it once was but I do think their strategies need analysis.

I am not sure about your strategy for another/new association but we’ll take that discussion offline.

This discussion seems indicative of the problems faced by any certification effort. If people aren’t prepared to engage with the SIA and sort out their grievances with the process then it just isn’t going to happen. I don’t think Rob Long’s fragmentation approach is going to work either (any more than it has worked for any of the political parties). The accountants and engineers seem to be able to perform the task of supporting the status of their members so I don’t see why the SIA can’t do this. If we are to have any credibility with our respective employers then we need to have a guaranteed skill set and certification can be part of this. The emphasis on University courses is not unusual either and I don’t agree that these things are excessively expensive to get. Someone quoted $40,000 to go from Grad Dip to Masterate. There are Masters by coursework available for a great deal less than this that can largely be completed online. If you don’t invest in continuous learning then it is difficult to see how you would maintain your competencies. One thing that is important is to ensure that the person teaching has the relevant expertise and is not just “holding themselves out” as an expert. Check that your lecturers PhD is in a relevant subject as the doctorate could be in some obscure arts subject that has nothing to do with safety and health. Check that they have current industry experience or at least some links to the industry in which you work. If we don’t organise to reach professional status then we run the risk of being replaced by safety engineers, because Engineers Australia supports their members status and requires professional development. If you were an employer who would you hire?

Kevin, people don’t work ‘with’ the SIA because the nepotism of the SIA won’t ‘work with’ them. It doesn’t matter how highly qualified or expert you are, they would prefer an insider with little knowledge to write in the BoK than an expert who they don’t like. The way I was treated by the SIA is just outrageous. There is far too much territory invested by individuals in the SIA journey to let go and collaborate. It is a toxic organisation and unrepresentative at best. I am working towards a new association next year where people will get value for their membership and will be able to proceed with an alternative accreditation process. If the SIA delight in alienating people then lets see how they cope with a bit of competition.

Dean, I think I have mentioned that the SIA needs a public makeover to capitalise on its organisational restructure. This won’t erase the past but many people and organisations have had to work through and rebuild from reputational damage.

That the SIA has proposed the certification process immediately loads the process with baggage that it should not have and is a distraction. No matter how the certification is presented and Councils or Boards mentioned, the SIA remains integral to any scheme’s administration.

It would have been ideal for someone else to initiate a certification process but no one did. The initiative of the SIA should be acknowledged and perhaps those additional organisations should engage with the SIA and begin to build the robust, independent and transparent process that the OHS profession seems to need. Perhaps we should start with the SIA but finish with a different process.

Raheel, I agree also that socialization in university courses is useful but, as I have a 20-year-old studying his uni exams at the moment, I think the growth in distance learning has shown that this option is going to stay. In this case, the SIA and others need to look at developing socialisation techniques that equate to the physical networking and the building of skills. The SIA seems well placed to be suggesting solutions to this issue rather than defaulting to the existing situation. I would like to see some innovation.

Kevin, a great summary that brings together the many concerns of those who have followed this conversation. I support the concept of safety practitioner certification, though believe that the SIA model is deeply flawed. The dogmatic behaviour of this institutions’ hierarchy has done nothing but alienate many safety practitioners, and cast a shadow over an important conversation.

As suggested by Rob Long above, I’d rather see regulatory bodies take the lead in this initiative. This should entail; inclusion of other industry stakeholders (as the SIA has selectively ignored many), transparency in decision-making, alignment of certification with practical learning and CPD objectives, and a focus on meeting industry needs.

A very well-rounded article Kevin, thank you. I too see the value in certification however feel that the SIA’s approach thus far falls into the unpromising spectrum.

With regard to further education online, I find the SIA’s view in this area interesting: “A number of providers of OHS education in the tertiary sector are offering courses by distance education. While this mode of learning suits the work and life demands of many people the Safety Institute of Australia has concerns about the quality of the outcomes of such programs.” This is supported by its view that interaction with peers, lecturers and mentors is essential for developing the skills needed to become an effective OHS professional – communication, critical thinking, analytical skills etc.

Whilst I agree with this view, perhaps the SIA can see merit in increasing the output and accessibility of workshops facilitating such live interaction to accommodate those persons for whom distance education is really the only viable means of obtaining the tertiary education required to qualify them for certification (inadvertently broadening their knowledge in the process). Not sure that this would assist in its elitist persona at all, as touched on within the article, but the idea is to provide the SIA with a degree of confidence (no pun intended) over the individuals it certifies, and perhaps assist in encouraging those in the industry who haven’t quite warmed to the idea as yet.

Having worked in Canada for a number of years they have what is known as CRSP – Canadian Registered Safety Practitioner standing. When it originally came out it involved written exams over the course of many hours. As demand grew due to businesses demanding CRSP certification this had a flow on impact to the authorising body. To overcome this the written exam became 100 multiple choice questionnaire – in effect diluting the process. This is an area where SIA needs to consider.

In regards to formal qualifications I feel that it is up o the individual to make the effort and not a body. Pathways are fine but nothing’s prevents doing further education online via correspondence. It has never been easier to get a degree online and costs are tax deductible for now.

Simon, the SIA has had representations from the North American bodies in the past. I know as I participated. The SIA was not clear on why these approaches were rejected for the current process but I know the examinations were seen, at the time, as too different from the Australian legal and OHS system.

There is a great deal to be said for a totally independent certificating body but the SIA is not proceeding this way.

Kevin, excellent review. It touches upon many, if not all, aspects of professional certification. There is clearly a worldwide drive towards ‘a paper that proves’ a person is capable of ‘doing something’. Mostly the drive comes from the market as well as a government. There are notable differences between certification scheme driven by governments (e.g. high school teachers, medical professions, barristers) and those driven by a market (e.g. scaffolders, electrotechnical inspectors). Government driven certification generally gives the professional more independence/ status (e.g. barristers) and higher income (teachers being the exception). Market driven certification works only, when the ‘doing something’ is very clearly defined. Where this is the case, the income doesn’t get higher, but rather lower and narrows in range.

Bringing this back to certification of safety professionals, I question whether it will work, because (1) there seems to be little government support and (2) the field, the “body of knowledge” is too fuzzy/ wide/ diverse.

The question for me is not so much about accreditation but the governance of it. I wouldn’t trust the SIA with a Primary School dress up day let alone such an important thing as accreditation. The assumption by the SIA that they should take the lead on this is nonsense given their track record. It is simply a territory grab for an ailing institution. I would only support a government statutory authority body in such a matter. The trail of toxicity towards the SIA (which they have created) makes it totally ludicrous that they should undertake this task. Looks like its time to start lobbying government and opposition and alerting them to the real nature of the problem. Just look at the nature of their membership and there are more safety people out of their fold than in it so, in what way are they representative of what?

Kevin, thanks for your great article. I tend to agree with Dr Robert Long’s viewpoint. There are indeed many concerns with the approach taken by the SIA. I was particularly interested in the proposed certification categories. Applied to my own circumstances I would be categorised as a Certified Generalist OHS Professional although I have held senior OHS roles and have over 15 years OHS experience – but I ‘only’ have a Grad Dip and cannot afford the $40,000 it would cost me to complete my masters!

I can well understand the questioner walking out if, as you report, the SIA’s response to their legitimate question was “Why not?” Lack of understanding indeed and a flawed process to boot…

Utmost regard for Malcolm having trained under his tutelage, but concerned about SIA approach and apparent gaps in info (should I say gaping holes and real intent.

1. Are they wanting to run the process and charge a fee?

2. levels of certification but 3 levels in their model all have the same qualification – where does this leave one?

3. Some apparent understanding or lack of qualifications – especially if it is true that 60% of their members do not possess formal qualifications.

4. Are they counting Cert 1V OHS or not. If not and the facts are correct as they stated them, one must query whether it is a safety organisation or just a group of interested like minded persons

5. Leaning towards university does not address the issue of “competence”

I am aware of one such learned institution where a professor teaching safety degree course teaches that a JHA is the main risk assessment tool – Scary stuff when you are out in the real world.

Need to consider other training and qualifications in concert with OHS training to get a broader picture of the reality of competence across a range of areas.

Need to get all qualifications aligned and especially content of courses as there appears to be quite a bit of variation and ideals pushed in parts which would not be helpful in setting up a certification that might be nationally recognised.

Stephen, my understanding is that yes, the SIA will be charging a fee for non-SIA members who wish to be certified. This fee structure varies with the number of criteria that the applicant meets. The SIA is relinquishing its current grading structure over time as people transition to certification. There was considerable discussion on this transition process.

The 60% figure certainly raised eyebrows at the seminar and provides a different context ot the certification process or rather encouraging people into the process.

On the matter of Cert 1V OHS, the SIA said

The SIA seemed to think that the issue of competence was addressed by focussing on capabilities. This may be the case but is an example of how the SIA needs to be speaking the language of industry sectors and businesses. If on asks about competence and the answer is capability, the message gets muddied.

Additional training in non-OHS areas was discussed but is seen as outside the OHS certification proposal. To provide the best OHS advice, I believe it is essential that one is trained separate to the OHS academia and has a strong understanding of safety outside the school books or, even the OHS Body of Knowledge.

The SIA emphasised that the certification seminar was not about accreditation of courses but the certification of individuals.

I encourage readers to put some of these questions to the program coordinator at info@ohscertification.org.au

Kevin, has AIOH’s (Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists) certification system been examined in light of this? This appears to be a reasonable model. It is disappointing to read of SIA’s response “Why not?” to those lacking university qualifications – as for us who lack a university degree, there are real barriers to entering Safety Education at that level – not withstanding possession of VET-level safety training.

Kevin,

A succinct and objective summary of where things stand. There is no doubt in my mind that some type of “certification” process for safety “people” is required – I am just not convinced that SIA is the right organisation to “sponsor” this?

The need to establish a standard of advice has never been starker in my mind. I recently had a safety consultant and a safety manager both determine that the cause of an event was that worker’s did not run out of the way fast enough from the emerging hazard, when it was clearly a failure of an isolation system. An extreme example, perhaps, but the inability of safety people to technically define safe (acceptable level of risk), hazard (presence of potentially damaging energy), and risk (chance, closely related to exposure) is a fundamental problem, only solved in the long term by an agreed and taught taxonomy. The continuation of “measuring” safety by injury counts remains a hideous misrepresentation of a manager’s performance; after all, he/she can’t control what a doctor decides, but it remains the noisiest and most useless of measures, continually promoted by those who want to call themselves professional.

The advice given by a safety person can have serious ramifications for a company. It you seek advice from a certified account (etc), why not from someone who has the same ability to impact the performance of the entity?

Kevin! Another amazing article. Such detail, I felt like I was on a long journey. No other comment.

Hi Kevin;

There are so many areas of concern in the proposed approach taken by the SIA in seeking a program of certification of professionals. Let’s just consider one.

A quick Google of the term ‘profession’ provides us with the following definition:

“A paid occupation, especially one that involves prolonged training and a formal qualification”

It would follow that of 60% of the SIA’s members do not have formal qualifications above a Cert IV, a reasoned argument could be made the SIA does not represent a profession but are merely an association of like minded people.

60% of members would not qualify as practitioners or professionals under their guidelines. So what quality does this association bring to the debate?

By any estimate, if certification were to come in tomorrow, 60% of SIA membership would effectively be unemployable or uninsurable.

At some stage the SIA needs to focus on its non-members and provide a basis for recruitment. This continued attention to the considered few will only deepen the alienation of non aligned ‘professionals’.

Mark, the SIA considered taking action against me when I took the President to task on how representative the SIA was of the OHS profession almost 20 years ago. He complained that the estimated 18,000 OHS practitioners in Australia should be members of the SIA, a group of around 3-4,000 at that time. I asked whether the SIA could claim to be the leading OHS organisation if 15,000 practitioners chose not to be members. I got into trouble for that.

I note that over that time, the SIA membership has rarely exceeded 4,000.

The discussion on certification has only just gathered momentum but I think the SIA needs to convince the community and business that certification is a necessity for improving the quality of OHS advice provided and that the SIA is the appropriate organisation to run it.

The SIA could claim that, technically, certification is being run by an independent Board or Council but, as far as I can see, the SIA funds the process and administers it. There is enough rigour in the proposed certification process that this should not be a problem but the SIA role needs clarification if the system is to be seen as truly independent.

Interesting. Definitely believe OHS practitioners should be certified. Some 10 plus years ago IFAP in WA was pushing for this and sponsored the WA chapter of the American Society of Safety Engineers as the first step to rewriting the entrance exams for being certified. This was in an effort to ensure that the certification of safety professionals was international. It was going to be the Australian chapter but due to the protests of the SIA, became the WA chapter. I believe that due to a lack of interest/support, it is almost defunct now, not sure as I have not seen anything for a while.

Good luck with the effort. I will support it.

Malcolm, recently the SIA entered into a formal relationship with IFAP so I am not sure where that leaves the ASSE process.

There have been moves for several years or a WA chapter of IOSH but the IOSH criteria is restrictive and the membership in Australia is sparse. There are rumours of another attempt at IOSH in the Australia/Pacific region but the SIA certification attempt complicates it further. It shouldn’t, but it does.