Several long and involved phone conversations resulted from last week’s articles on Australia’s Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Body of Knowledge (BoK) and its role in accreditation of tertiary OHS courses. It is worth looking at the origins of some of the issues behind the research on these safety initiatives.

Several long and involved phone conversations resulted from last week’s articles on Australia’s Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Body of Knowledge (BoK) and its role in accreditation of tertiary OHS courses. It is worth looking at the origins of some of the issues behind the research on these safety initiatives.

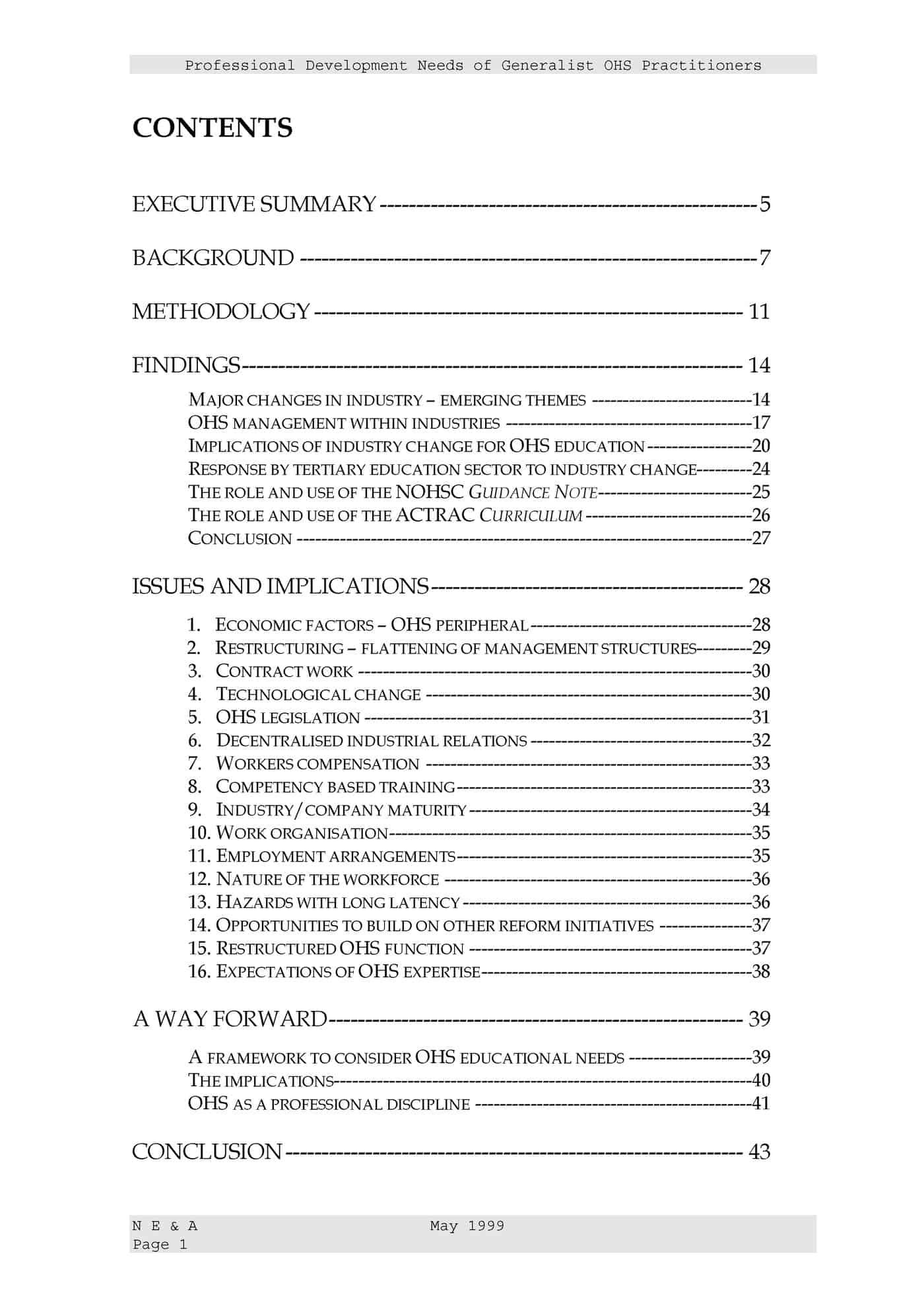

One important document was published by the National OHS Commission (NOHSC, a forerunner of Safe Work Australia) in 1999 – “Professional Development Needs of Generalist OHS Practitioners“* . This NOHSC document continues to be referenced in the continuing debates listed above and illustrates the need to understand our recent OHS past.

The Executive Summary of this 1999 document identified the need for a body of knowledge:

“….The integration of OHS into mainstream management is apparent, particularly in larger businesses, and with this comes an increase in the range of managers and other professionals involved in OHS. The outsourcing of OHS expertise in this context is also a growing trend.

These changes have considerable implications for the role and development needs of the OHS practitioners; indeed the role and function of the OHS practitioner varies considerably from one organisation to the next.

This paper suggests that these changes have increased the necessity for everyone involved in OHS, from senior management through to the OHS practitioner, to have a common core of OHS knowledge, skills and attitudes.” (emphasis added)

In the last 25 years, there has been a growth in external OHS advisers just as the internal corporate legal services have been outsourced. It is suspected that the trend identified here has continued, but contemporary evidence seems scarce.

Roles and functions do vary considerably just as OHS needs vary between small, medium and large companies. OHS practitioners need to be able to able the basic OHS principles across this industrial variety.

These skills should be based on a “common core of OHS knowledge, skills and attitudes”. NOHSC’s document identifies three crucial elements for developing an OHS professionalisation:

- Knowledge

- Application

- Attitudes

The OHS BoK is only one of these criteria, albeit an important one. Knowledge without application is interesting but OHS is about the reduction and prevention of harm. It is about action and application. “Pure” knowledge in the OHS discipline seems almost contrary to OHS’ purpose.

The inclusion of “attitudes” raised hopes that this area would be defined and discussed, but it was not to be, in this report. The report conclude that:

“Everyone (OHS practitioners at all levels, managers, technical specialists) involved at whatever level of OHS function, needs a consistent core of OHS knowledge, skills, abilities and attitudes/values (to be defined).” (emphasis added)

The quote implies some equivalence between attitudes and values which fits with some of the values-based OHS training that has emerged since. That training largely become behaviour-based training that has been ridiculed by significant sectors of the OHS profession, primarily, because of the over-estimation of its significance and influence.

It may be that what was intended when discussing attitudes was an examination of OHS as a component of organisational culture.

Specialists and Professionals

Australia’s safety profession missed its chance to apply accurate and simple categories of skill. Rather than introducing “Generalist” to common parlance, it had the opportunity to mirror the structure of medicine where there are General Practitioners and Specialists within a Medical Profession. Such a split would have been more palatable to the safety professionals and not require any explanation to OHS clients and end users.

The NOHSC report discusses Specialists:

“OHS specialists (e.g. ergonomists, hygienists, physicians etc.) and those involved in developing OHS strategy need to add to their OHS technical skills a broad base of business knowledge and skills, and the capacity to be change managers, critical thinkers and problem solvers, so that they can implement measurable cost effective solutions.

Expertise in occupational health, in addition to safety, is also important to deal with emerging occupational health issues.”

(Good to see health specifically mentioned)

In a brief discussion on OHS as a profession NOHSC asked a crucial question (emphasised below) for which evidence, other than anecdotal, still seems to be missing.

“Professional ‘status’ certainly impacts on the capacity of OHS practitioners to gain access to and influence critical decision-making. To the extent status is earned, the relatively low status of OHS practitioners reflects perhaps on the actual performance, competence and professionalism of OHS practitioners. Is the discipline able to demonstrate that it is able to deliver cost-effective responses to OHS issues in the business environment? After all, OHS is often referred to as ‘common sense.’

The NOHSC report could be dismissed as simply of historic interest but there is a tendency in OHS to ignore the recent past and to accept each new guidance or other initiative as if there were no precursors. It is important that we understand how current actions have evolved. The fact that the NOHSC report currently exists only in hard copy libraries, and likely only those few libraries of Australian OHS regulators, is evidence of this process.

There is a history to everything we do, all the decisions we make and the initiatives we apply. To better understand what is happening now, we must look to the past, even if it is only 25 years ago.

*SafetyAtWorkBlog has contacted Safe Work Australia who has agreed for me to make this document available..

Mark, I think that the term of safety professional is a bit of a misnomer, given that safety has its own legislation (both Federal and State) that places the onus on employee and employer alike, insofar as their mutual covenant to their safe behaviour in the workplace is concerned.

This is not to say that the likes of yourself and Kevin are not professionals, because realistically you both are – but not everyone who is employed in a safety role is.

Can a person be a safety professional? I think not. I’m of the opinion that you can fulfill the role of safety professional if you have the intellect and capability, but as safety itself is not recognised in the broader industry as being a profession, it therefore is not.

I remember a heated debate which included Col Finnie, whereupon he correctly opined that the tertiary qualifications of some lucky individuals did not necessarily make them capable, let alone allow them to call themselves professional. I agree with this sentiment, although I do not limit it to safety alone.

Is safety a discipline? It is when placed in the context of a workplace with a dedicated position attached to it. Notwithstanding the cottage industry which is referred to as safety over the last 3 -4 years, historically safety roles were filled by trades peoples whose experience on the job benefited them in the safety role, as they could then apply the safety knowledge and requirements into their workplace.

Undergraduate studies in OHS were traditionally the domain of those seeking a career in government or the corporate landscape, with post graduate and doctoral studies in OHS for those already in these positions, and who sought to enhance their careers accordingly.

To come back to the question under discussion here, namely is ” … able to deliver cost-effective responses to OHS issues in the business environment? ..” I would suggest that irrespective of the individual in a dedicated safety position, the legislation itself dilutes any absolute requirement for either discipline or profession by using the word “practicable”.

.

Mervin,

I think there is an opportunity to debate whether safety is a profession, discipline or neither.

There has been a contradictory argument within safety over the years. On one hand, we should be recognised as professionals because of the wonderful skill set we bring to business etc…etc. On the other hand the old mantra of ‘safety is the way we do our business’ or rather it is integrated into everything we do. Either we are needed or not. (though I still lean towards the view, that as an employee my job is to drive my own redundancy…perhaps that’s why I moved into consulting to ensure my own future.) In many regards, we still look at safety as an activity that is extrinsic to business planning. It’s so specialised that you need to engage a health and safety guru at $100k + per year.

The discipline of safety has flipped and flopped considerably over the years. I remember when I first started, 20 plus years ago it was via a Diploma in Applied Science with a focus on the Scientific Method. Then we moved into the bizarre world of safety as a behavioural science…drum roll…BBS and Values Based Safety… finally dumbing down into regurgitation of guidelines and regulation sponsored by various regulators. Now I am going through the final stages of a BOK based Masters and find myself asking where is the grist in this subject matter. Interestingly the Masters OHSE is administered by the faculty of business and law, but has little consideration of the role of OHSE in business.

Do these qualifications make me a safety professional? Not at all. They do reinforce my role as a business professional first, with an expanded level of expertise in OHSE management.

Mark, recently a reader called me to say that OHS/WHS does not “sell” itself well. I have seen many dodgy safety salespeople in my time (many of them OHS professionals) and always associate selling with spruiking but the older I get the more I understand that selling something is about communicating its merits for mutual benefit.

If this is the case, OHS needs to sell itself now as much as it ever did.

The comments above show that this OHS communication lark is not as simple as it seems and that the “soft” (but powerful) skills of communication is vital to progress the OHS profession and its application.

Of course, this communication must also be supported by transparency, evidence, independent thought, mature tertiary education and sound professional associations.

Mervyn, I agree with your point broadly, but do question the concept of whether health and safety is either a discipline or profession.

The NOHSC’s three criteria; knowledge, application and attitude are a sound base, but unfortunately the interpretation of these terms quickly becomes muddled. Is a person well versed in behaviour based safety knowledge and practices that displays and demands the expected attitudes, a safety professional? Certainly within their field of expertise, they may exhibit the knowledge, application of that knowledge and an appropriate behaviour based attitude, but is that transferrable to an organisation requiring a more liberal approach? We have many people delivering aspects of WHS in extremely closeted (or perhaps cossetted) environments where experimentation, creativity and innovation are not encouraged. Is an Degree qualified Occupational Hygienist a professional with the same standing as a part time Cert 4 OHS Officer working in a predominantly admin/work station assessment role. These are all vastly different roles and questionably completely different trades, yet we still persist in calling them WHS Professionals. Just because I make a quid from having WHS or OHS in my JD does not make me a professional.

Critically, I think the capacity to ‘deliver in the business environment’ must drive the ‘professional’ debate. It is difficult to see anyone as a professional if they cannot engage across the spectrum of business, from the Executive to the shop floor (though I’m going out on a limb to say that I’m not sure the shop floor is critical in this definition…a debate for another day perhaps). The engagement should be driven by meaningful, solution based conversations using appropriate language and applying an understanding of the machinations of operating a business to ensure the correct context is in place.

Let the debate continue.

Is the discipline able to demonstrate that it is able to deliver cost-effective responses to OHS issues in the business environment?

The answer, quite sadly, is No.

I think I have to agree Merv. One of the points of the article is that such questions have been asked in our recent past.

Just as there are people who still push “putting the H back into OHS” when the question should be “why was health not given the prominence it deserved, and was expected, in the OHS laws?”, the analysis of the success or otherwise of the OHS profession in changing workplace safety still does not seem to have been researched.

For instance, each year Australian OHS regulators take justifiable pride in saying that fatality rates have declined consistently over the last 4 decades but, other than the introduction of OHS laws, the causes of this decline remain vague. The role of the OHS profession in this decline is particularly vague, especially when one considers that the OHS profession remains confused about its role and purpose. Could a confused profession claim any influence in the decline in the fatality rate? Probably not, and if this is the case, what is the purpose of the OHS profession?