By Melody Kemp

Walking my dog along the Mekong in Vientiane, new piles of building rubble litter the river bank. The capital has long had a problem with plastic waste, but as unbridled wealth spreads and humble buildings are replaced by garish McMansions, building rubble is turning up in the general detritus. Among the bricks was what looked like the residue of shattered Asbestos Cement sheets; but without necessary skill and a microscope how could anyone tell?

A Vietnamese trader arrives. He rifles through the remains, takes a few of the bigger bits, tosses them in the trailer behind his bike and leaves with a nod. Later, in the main street outside a hardware shop, a large box of mixed waste lies waiting for collection. Laos do not separate their waste at source and while there may be provisions for hazardous waste, procedures are not observed. Out of date drugs, toxic chemicals, poohy nappies are tossed into or along the river; are burned or go into general land fill sites. Or are scavenged.

Those few minutes epitomised some of the social/behavioural difficulties of controlling hazardous materials in any of the Mekong nations. Things are changing thanks to the efforts of ex-ILO Technical Adviser Phillip Hazelton. Now back with APHEDA, he is coordinating a regional effort to ban asbestos. He recently announced the formation of Lao Ban representing pertinent government agencies including the Lao Federation of Trade Unions, also a government agency.

Sounds easy right? I previously wrote about asbestos in the Mekong region. This story is more about the logistics of what might be needed to achieve a ban and control of this notorious carcinogen.

Aussie Commitment

There is high-level support for a ban from Australia’s delegation to Laos. Recently Professor Ken Takahashi, Director of the NSW Asbestos Diseases Research Institute, spoke at a gathering of Lao Ministers, senior officials representatives of the Wold Health organisation (WHO) and civil society agencies, to underscore the case for banning. He seized on the current lack of cases of Asbestos Related Diseases (ARD) as evidence that imposing a ban now would prevent future deaths.

Andreas Zurbrugg, Deputy Head of Mission told me that the Australian Embassy’s involvement ‘is not simply ceremonial.

“We are active through workshops and through lending influence. Lao is at a stage when banning asbestos now will prevent a lot of future illness and deaths. Asbestos is part of the Australian story, albeit a shameful one. We feel we are in a good place to take this on.’

‘It’s a long-term process we realise. We have been involved with the asbestos issue in the region for over ten years. “

Takahashi told SafetyAtWorkBlog:

‘It was clear that the MOH (Ministry of Health) and MLSW (Labour and Social Welfare) support a ban, but Ministry of Industry (MOIC) (and perhaps Science & Technology) were clearly opposed to it. I trust the former ministries regarding their position on asbestos. As for the latter, I suspect that the officials have already been influenced by the pro-chrysotile lobby. The Minister of Health Assoc/Prof Dr. Bounkong Syhavong seemed very supportive.

The Director of the Department of Hygiene and Health Promotion (DHHP) in MOH took the lead of the conference [and] seemed to be aiming at a middle ground across ministries. Hopefully, the Minister’s position continues and prevails. Dealing with asbestos requires inter-ministerial coordination, and I assume (hope) an inter-ministerial committee will take the lead.

Because the WHO’s prime contact is the MOH and the WHO already worked with the MLSW and MOH to establish the Decree on OSH (I served as WHO consultant last year for this purpose), the drivers will undoubtedly be the MOH and MLSW, with support from the international organizations.’

The Ministry of Health wants to ban all types of asbestos by 2020. However, the more powerful Ministry of Industry and Commerce (MOIC) is going to be the test. Hazelton told me

“They are convinced the lobbyists are right… They keep saying it’s harmless. Small fuzzy fibres that dissolve in the body.”

Well Thatched

Our house in Bali was thatched. Over 40 centimetres thick, the roof lasted well over 25 years and kept the house well insulated. In Europe thatch was, and is, iconic.

But in development circles it’s an indicator of poverty. Many ethnic groups celebrate harvesting and roofing a house with elaborate ceremonies, not considering it a privation. Ms Laine-Barlow an epidemiologist told me

‘When we do surveys, there are only three types of roofs listed. Tiles, thatch and (corrugated) iron. I would have no idea if a roof was made of asbestos. I only know that thatch is regarded as lower socioeconomic status.’

In response, the number of tile factories in the city and districts increased from 2 to 16 in a few years. This would not be a matter of concern except that a tour of building supply shops nearby indicated no matter what colour tile you choose, all the brands on sale contained asbestos.

Russia, China and Kazakhstan are only happy to supply Chrysotile asbestos to the point that Laos now produces enough tiles, brake linings, textiles and other components, to allow each Lao 1.2 kilograms per head.

Identifying asbestos is a challenge in a nation where basic laboratories are only now being established, and qualified inspectors are rare. Asbestos competes with numerous other major health issues for attention. For instance, liver cancer kills far more each year and Lao’s only breast cancer specialist told me he sees 1,000 women for treatment each year and the number is climbing. ‘Most report far too late and there is little I can do.’ From experience that could apply to most cancers.

And, of course, there are always traffic accidents. In a nation that boasts signs saying, ‘Drink Don’t Drive,’ crashes kill up to three people per night in the capital alone.

Dr Doavone of the Cancer Centre on the city’s outskirts, sighed,

“‘The Russians took a group of ministry (MOIC) people to show them the mines in Kazakhstan and Russia. They gave them food and vodka. The Ministry people were impressed by the size of it all and that it is a good product.”

Sri Lanka felt the backlash from Russia when they stopped importing asbestos. No doubt Lao would find that being a Communist comrade is of little value in the hard world of resource economics.

But Doavone was adamant.

“We cannot buy the health of people with money. Humanity must be more important than short term greed… We talked to small scale contractors. They were scared and decided to make something else. It’s not just workers, it’s people in the community who are at risk.”

When I first came to Lao, 14 years ago, few smoked, or they did so politely. Even Ministers would leave the room. Now clusters of saffron-clad novices and other young men light up. Young men who smoke are also likely to be construction workers exposed to asbestos products making them more vulnerable.

Doavone agreed that bringing experts to Lao, rather than taking Lao to Australia would be preferable, as experts need to appreciate the huge challenges the government faces.

“We can do histology and do basic imaging, but services are largely only in the capital. Long term treatment is very difficult. Who takes care of the children if one of the parents is ill or dies?”

In Laos, family are often expected to purchase drugs, feed and wash their sick family members, usually moving in, rather than visiting. Despite being nominally Communist, there is nothing benevolent about the government. Bodies, such as the Trade Union, are appointed as instruments of government leverage, rather than strident advocates, so change is necessarily incremental.

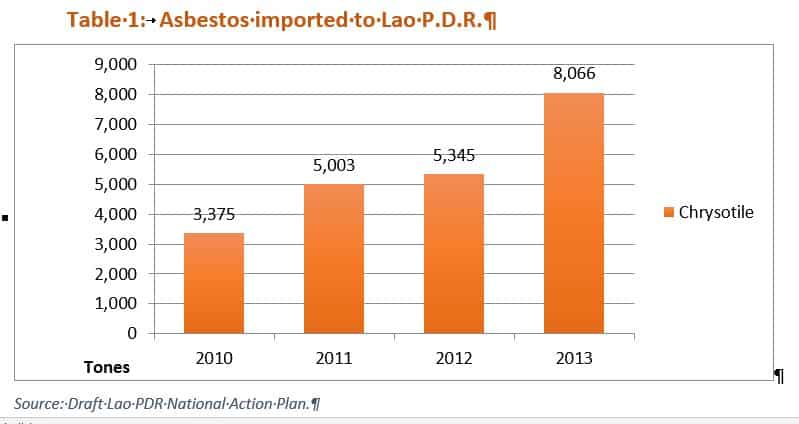

According to a national survey approximately 21,000 tons of Chrysotile was imported into Laos between 2010 to 2013 rising from 3,375 tons in 2010 to 8,066 tons three years later. Some factories imported raw asbestos independently while others bought from other importers who also produced asbestos products.

Professor Ken Takahashi adds

“Safer substitutes for asbestos-cement products such as roofs are polyvinyl alcohol, cellulose and polypropylene. They are only marginally more expensive than asbestos.”

But in a nation where the rich won’t pay 40 cents for parking, or 15 cents to have garbage taken away, preferring to dump in on the side of the road, can the poor afford the margin? Availability in remote areas and understanding of its importance may be other obstacles.

Collaborating with aid agencies so they modify the ‘solid roof’ definition to take into account the risk they are imposing, may be another.

Logistics

The survey concluded that over 500 workers were potentially exposed to asbestos based on their employment in the manufacturing of construction materials, car maintenance, boiler-making, import and exports trades, building and road construction/maintenance, and engineering.

The survey concluded that over 500 workers were potentially exposed to asbestos based on their employment in the manufacturing of construction materials, car maintenance, boiler-making, import and exports trades, building and road construction/maintenance, and engineering.

As the Lao economy industrialises and modernises, and as urbanisation progresses, the construction materials industry will continue to grow. There are also opportunities for export to neighbouring countries (NAP Lao).

Political and commercial decisions over the next few years are crucial for protecting the health of Lao citizens; as is understanding the complex and, at times, dodgy political landscape. It’s more a socio-political challenge than a technical one but one that must be met.

Phillip Hazelton and APHEDA have produced an open letter about some of the asbestos concerns