There are several initiatives throughout the world under the banner of workplace health that have little relation to work. They are public health initiatives administered through the workplace with, often, a cursory reference to the health benefits also having a productivity benefit.

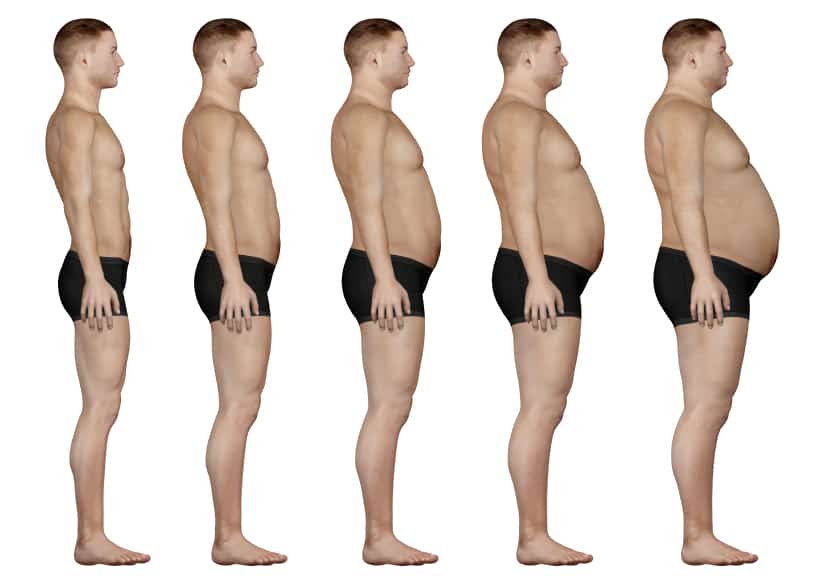

So is a fat worker less safe than a thin worker? Such a general question cannot be answered but it illustrates an assumption that is underpinning many of the workplace health initiatives. There is little doubt that workers with chronic health conditions take more leave but, in most circumstances, this leave is already accounted for in the business plan.

So is a fat worker less safe than a thin worker? Such a general question cannot be answered but it illustrates an assumption that is underpinning many of the workplace health initiatives. There is little doubt that workers with chronic health conditions take more leave but, in most circumstances, this leave is already accounted for in the business plan.

Sick leave is estimated at a certain level for all workers across a workplace and, sometimes, a nation. There is an entitlement for a certain amount of sick leave for all workers, fat and thin, “healthy” or “unhealthy”. It certainly does not mean that the entitlement will be taken every year but the capacity is there and businesses accommodate this in their planning and costs.

Remove this generic entitlement so that only working hours remain. Is a fat worker less productive than a thin worker? Is a worker without any ailments more productive than a person with a chronic ailment? Is a smoker more productive than a non-smoker or a diabetic or a paraplegic?

Before safety professionals accept the offers of free worker health checks or commit to a long and, usually, expensive program of “changing your company’s health profile”, it is very important that the costs and benefits of such initiatives are determined as they relate to one’s own specific workplace. It is vital that when considering a health program that alternate suppliers and services are comparable, that they can be benchmarked with each other. It is also prudent to have a provider specify the health outcomes of the program, to guarantee those outcomes and to provide a refund should the performance benchmarks of the program not be achieved.

To assist with achieving this last aim, it may be worth determining for one’s self the health profile of all employees through an independent assessor or auditor who does not also provide “health interventions”. In this way, you own the data of your employees, and you can use this as the benchmark when considering a range of programs and providers of health services, if such a program is needed at all.

Some of the workplace health initiatives echo the “blaming the worker” approaches from decades ago and that are hidden in the contemporary behavioural-based safety systems. The healthiness of the individual worker is the focus of health initiatives rather than looking at the potential contributory factors in a workplace.

For instance, we know that “shift workers appear to have increased risk of GI symptoms and peptic ulcer disease”*. Do we provide milk of magnesium or do we reassess the need for shift work?

In 2008, the Danish National Board of Industrial Injuries identified breast cancer after night-shift work as an industrial injury and compensation was granted in all but one of the cases dealt with at that time. How should this risk be managed, symptomatically or at the cause?

Although these examples both involve shift work, they illustrate the deficiencies and shortsightedness of most workplace health initiatives.

Such schemes have become trendy to have as if one cannot be an “Employer of Choice”, or just a good employer, without one. Most of these schemes are likely to prove to be a workplace fad with dubious long-term value like workplace gymnasiums, or fitness ball seating or back belts.

Many health schemes are expensive distractions that are hooked onto occupational health and safety programs because it is often too hard or time-consuming to investigate a workplace issue to its conclusion. The hesitation may be because sometimes the investigation may show that the structure of a business relies on a disposable workforce and to address the humanity of the workers would threaten the viability of the entire business. It is much easier to give the workers “happy classes” or tell them they are under-performing because they are obese rather than looking at the business model and asking the hard questions.

*”Gastrointestinal disorders among shift workers” by Anders Knutsson & Henrik Bøggild in Scandinavian Journal of Work & Environmental Health 2010 vol 36 no 2

Hi Kevin, Great reading your blog, this one gave me a lot to think about.

Stress, generated entirely at work, can have serious effects on an employee\’s health. From stomach upsets, lowered resistance to infection and the biggie, heart attack. I can remember many workers going home on the work provided bus grumbling (more than usual) about their bosses, the work load, the workplace, lack of amenities etc. It was not surprising to find many of them absent from work for short and long bursts and a few of them retired on medical grounds, most under 55yo.

Of course you can\’t make an omelette without breaking eggs but the thought that work contributes to premature illness and death is too much to pay.

Note: Orson Welles was a large man and this in no way impeded his work, Leonardo Da Vinci also large, see what he achieved, we need to be on top of \’fat bashing\’, it is discrimination, clearly.