At the recent Scientific Meeting of the Australia and New Zealand Society of Occupational Medicine (ANZSOM), Allison Milner stepped in for an ill Tony La Montagne and added value to his intended presentation on workplace mental health. This meeting is different from other conferences in one particular way, in relies on evidence and not marketing for its presentations. This difference made Milner’s presentation very powerful.

At the recent Scientific Meeting of the Australia and New Zealand Society of Occupational Medicine (ANZSOM), Allison Milner stepped in for an ill Tony La Montagne and added value to his intended presentation on workplace mental health. This meeting is different from other conferences in one particular way, in relies on evidence and not marketing for its presentations. This difference made Milner’s presentation very powerful.

Milner set the scene with a broad picture of mental health:

“1 in 5 Australians have a mental illness, which equivalates to about 1.5 million. And over 3000 people lose their life to suicide every year, and the vast majority of these people being men. But suicide affects far more people than those people who attempt or sadly lose their life. It affects their work colleagues, it affects people in our community and it affects our family.”

This “1 in 5” statistic appears often in Australian discussions about workplace mental health but often it is unclear whether this is an annual figure, only related to non-work issues and what is exactly meant by “mental illness”. Milner specified that 1 in 5 Australian will have a mental illness in their lives and that this is likely to be anxiety or depression and these two conditions are the leading cause of non-fatal burden of disease. This concision is rare but what is needed as the Australian Government;s Productivity Commission begins investigating the cost of mental illness.

Job Stressors

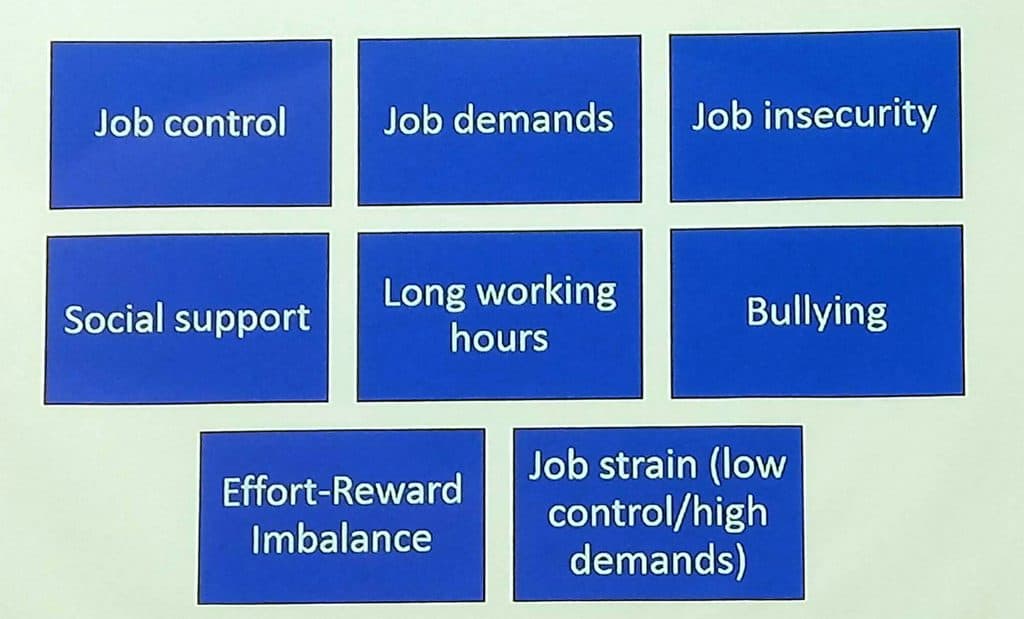

Milner was able to show research that clearly identified the job stressors and work design factors that contribute to poor mental health and all the costs associated with that. She, through La Montagne’s research, showed how the more stressors a worker was exposed to the higher likelihood of mental illness. These job stressors, in the image below, have been discussed before in this blog and are well-established throughout Australia’s occupational health and safety (OHS) and public health sectors but continue to be ignored by most businesses.

These structural and organisational elements are important to remember when discussing the mental health impacts of topical issues like the gig economy (job insecurity and long working hours) and precarious/casual employment and labour hire (Job strain and long working hours).

Prevention

Although prevention of harm has always been a core element of OHS legislation for a long time, symptomatic relief has often been seen as sufficient to comply, by both Regulators, businesses and the community, but this position is changing. The recent Senate Inquiry into Industrial Deaths included prevention in its terms of reference. Australia’s Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins, has repeatedly stressed the importance of preventing sexual harassment and the related mental trauma by addressing its causes. Milner pointed out the changing perception on prevention at a global level:

“The problems, the sheer prevalence of mental health issues and the extreme effect these have on people’s health have led the authors of the Global Burden of Disease to argue that greater attention needs to be paid to prevention. Focusing on the risk factors and the predictors of mental health problems and the broader societal factors that increase prevalence in burden. So, this suggests we need to move beyond the health system, we need to be able to identify and prevent these at their source.”

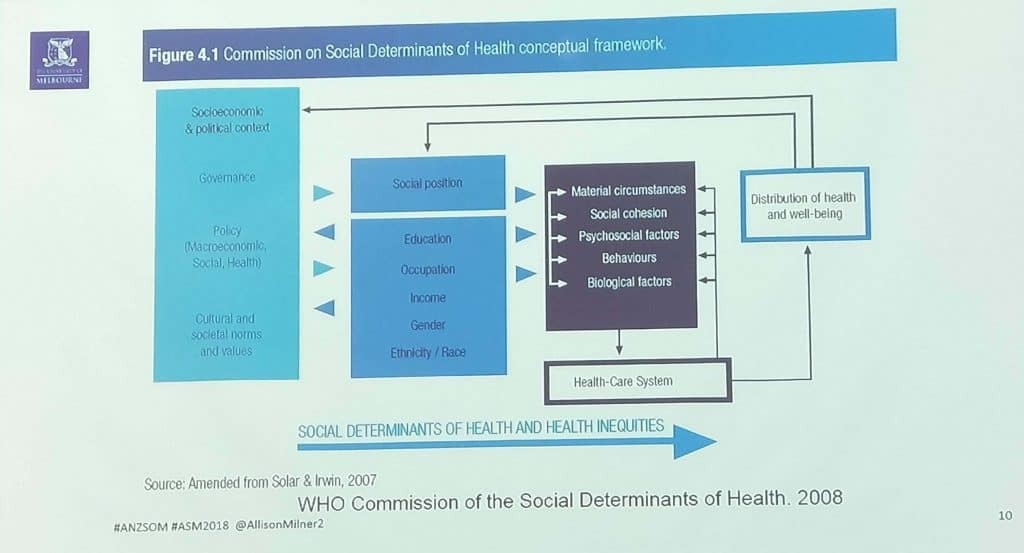

Depending on one’s attitude to prevention and workplace health and safety, the World Health Organisation’s model of Social Determinants of Health is either a framework for change or an insurmountable challenge. Milner used a 2008 model to illustrate her point about the interconnectedness of social and workplace issues. This graphical depiction of the framework, it has changed a little since 2008, should be closely considered by the OHS profession in determining their operational strategies.

Workplaces and Suicides

Milner’s comments on suicide, a particular area of interest in her research, is significant and illustrates her awareness of the societal context of causes and effects. She pointed out that, although certain professions achieve a lot of media attention on this issue, evidence shows that

“… the lowest skilled workers, …[in two ISCO categories] which is represented by machine operators as well as people working on ships, … and … ‘elementary people’, so cleaners and labourers, have a much greater risk of suicide than those people who are working with dentists, [for instance].

And the next greatest risk is among the service occupations and the farmers… The least risk of suicide are with, among those people with the most economic social power, … – managers, people that have the ability to hire and fire.”

The lesson from this is to not judge the severity of a problem by its level of media attention. These statistics do not identify what workplace factors may, if at all, be affecting the workers in these occupational categories only that the use of these categories may help in determining better intervention strategies.

Building on La Montagne’s research into job stressors, Milner’s research has shown that:

“…there’s also evidence in relation to suicide death, so those people who are exposed to job stressors, had 1.17 increased odds of suicide compared to those with moderate. And this result is most consistent for men who are exposed to poor job control.”

Many have said that the evidence of a direct link between workplace issues and suicide is difficult to determine without a suicide note, for instance, but from her research Milner is able to say that:

“…there might be some cordial evidence that the conditions people are working in at the time of their death are contributing to their risk of suicide.”

Suicide and Gender

But her research also pointed out some surprising correlations. There is a lot of discussion in suicide prevention about restricting access to the means of suicide, such as guns. Milner points out that suicides by gun declined after the gun buy-back scheme which resulted from the political response to the Port Arthur massacre, but that evidence shows that suicides by women are often greater than those of men.

“….females with access to means, had much greater risk of suicide than those without access. And this is explained predominantly by a high suicide rate among female doctors and female nurses. So, another study I’ve done looking specifically at doctors found that there is no increased risk among male doctors compared to other males in the working population, but there is an increased risk among female doctors. Interesting for nurses there was an increased risk among both male and female doctors. So the really other fascinating thing about this area of work is this intersection of gender …”

Occupational health and safety has largely ignored gender except as a categorisation of male- or female-dominated industries. The gender relations within those workplaces and how they affect, or are affected, by OHS interventions is rarely studied even though the importance of gender at work has been prominent since at least 1983 as this excerpt from Game and Pringle’s book shows:

Occupational health and safety has largely ignored gender except as a categorisation of male- or female-dominated industries. The gender relations within those workplaces and how they affect, or are affected, by OHS interventions is rarely studied even though the importance of gender at work has been prominent since at least 1983 as this excerpt from Game and Pringle’s book shows:

“Gender is fundamental to the way work is organised· and work is central in the social construction of gender. This is the deceptively straightforward theme of this book. Yet gender and work are rarely put together. When sociologists, political economists, or Marxists study the labour process they invariably ignore gender. The best they can do is make a token mention of the ways in which gender is manipulated by management to create disunity in the working class. On the other hand most studies of gender, ranging from sex role theory to psychoanalysis, are not informed by political economy or anything more than a limited understanding of the labour process. Our view is that studies of gender and studies of the labour process are incomplete unless they take each other seriously.” (page 14)

The relationship between gender and OHS has been part of that “token mention” for too long. The increased attention to workplace sexual harassment and its psychological impacts shows that tokenism has moved to mainstream consideration.

The Integrated Approach

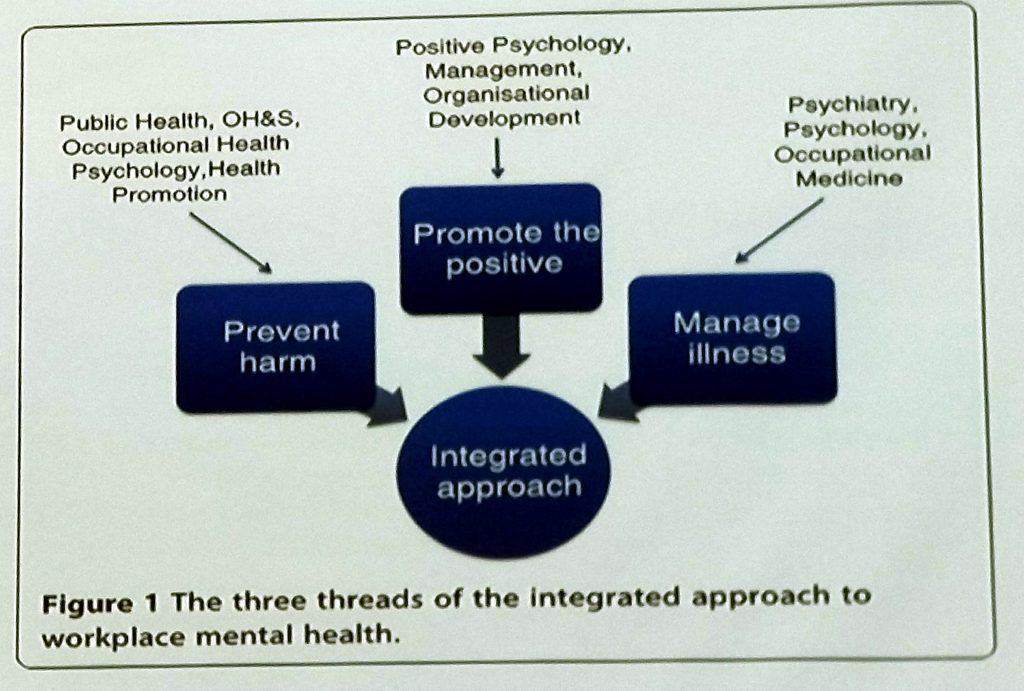

Milner reiterated the integrated approach to workplace mental health advocated by La Montagne since his 2014 research, and which seems equally applicable to any OHS strategy.

“Promoting the Positive” has been shown to have a positive benefit on workplace mental health but this should not be applied uniformly across the workforce. Milner points out that

“A study we did a few years ago showed that high positive mental health buffered the effects of job stress on mental health. So those people who had job stress at time, one had poorer health at time too, but then when we looked at whether they were also received high, they also had high psychological well-being, we found that the effect of job stress lessened. But these results were mainly effects seen among those people with pretty high levels of mental health to begin with rather than those people with low levels of mental health, so that’s important as well in terms of how we understand these interventions to work across the working population.” (emphasis added)

This point is significant for those thinking about introducing a positive psychology program to already dysfunctional workplaces.

Milner’s (and La Montagne’s) presentation at ANZSOM was thorough and confronting but also more influential than other conference presentations because of the level of evidence, referencing and direct research. Milner summarised the presentation pointing out that mental health problems are very common and they relate to both individual AND organisational issues. The workplace determinants of mental ill-health are able to be modified. She pointed out that some occupations are more at risk of suicides than others and that factors other than psychosocial exposures apply.

She also emphasised that a “ground up and a ground down approach” is needed to design mental health interventions. Any intervention needs to be tailored to a workplace and that this must be, and must be seen to be, genuine. Importantly, the evaluation of any intervention needs to be included in the design of that intervention.