Yesterday’s article on Comcare’s recent charging of two organisation over workplace-related harm to others generated so much interest that I have (re)published an article from 2016 that analysed an earlier, similar issue. Please also read the comments below and consider adding your own.

Australia’s work health and safety (WHS) laws confirmed the modern approach to workplace safety legislation and compliance where workers and businesses are responsible for their own safety and the safety of others who may be affected by the work. The obligations to others existed before the latest WHS law reforms, but it was not widely enforced. The Grocon wall collapse in Victoria and the redefinition of a workplace in many Australian jurisdictions through the OHS harmonisation program gave the obligation more prominence but has also caused very uncomfortable challenges for the Australian government – challenges that affect how occupational health and safety is applied in Australian jurisdictions.

Recently, these changes have been investigated in the context of the Australian Government’s occupational health and safety (OHS) obligations to those who are being held in regional processing centres (RPC) in Nauru and on Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) Manus province.

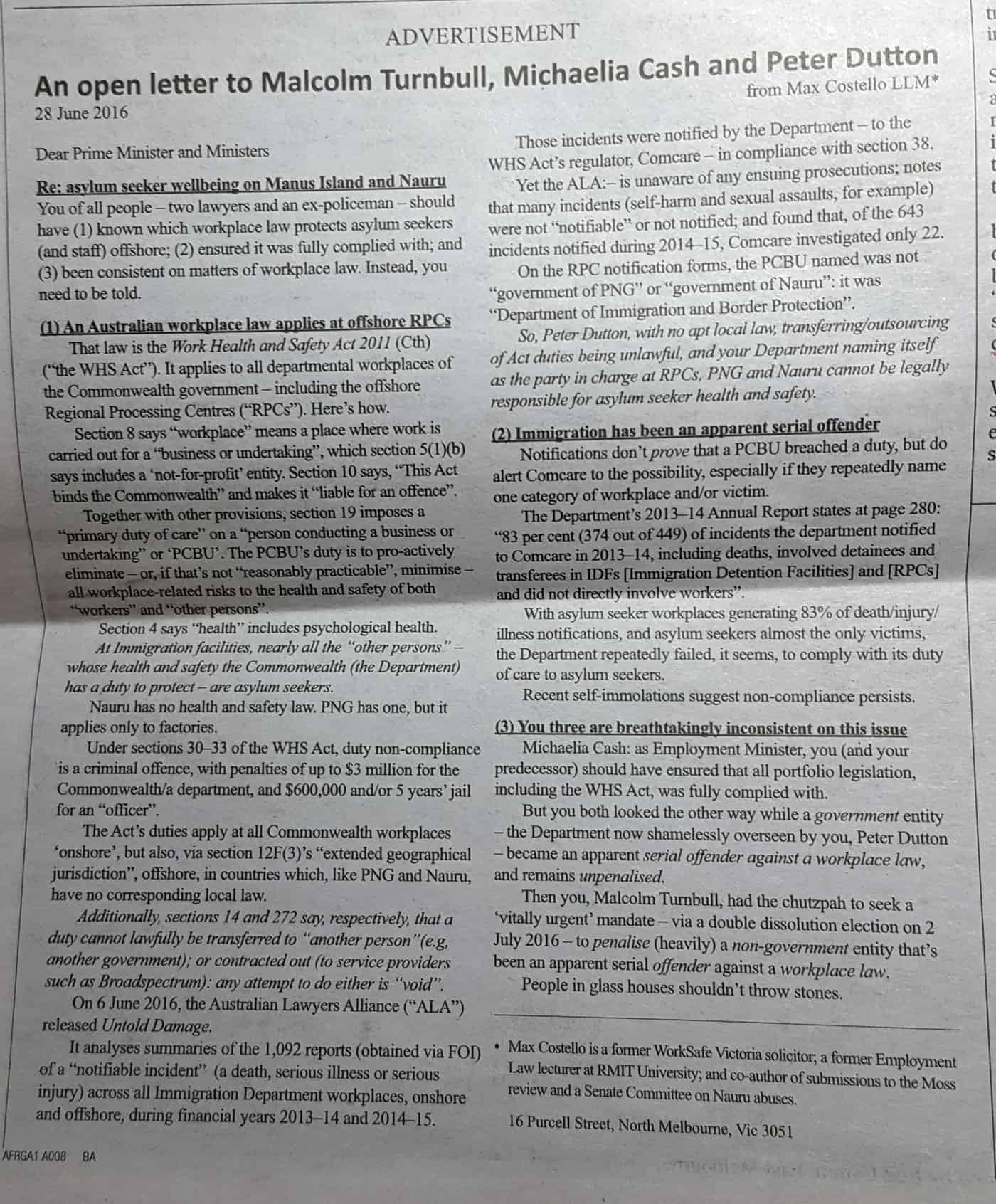

Former WorkSafe Victoria prosecutions solicitor Max Costello published an open letter to the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, Minister for Employment, Michaelia Cash, and the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, Peter Dutton, in the Australian Financial Review on 28 June 2016, pictured right. The letter outlines Costello’s argument that the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth)

“applies to all departmental workplaces of the Commonwealth government – including the offshore Regional Processing Centres.”

(Many of Max Costello’s points can also be found in this article.)

The RPCs have been criticised by human rights agencies and advocates, with Nauru having:

“Hunger strikes and self-harm, including detainees sewing their lips together have been reported as occurring at the facility. Attempted suicides were also reported.”

Manus’ RPC has had

“..a series of protests by detainees at the centre escalated into a serious disturbance, and subsequent events resulted in the death of one detainee: Reza Berati, a 23-year-old Iranian asylum seeker.“

Costello points out that almost all the “others” in these locations are asylum seekers and detainees. He writes that

“The Act’s duties apply at all Commonwealth workplaces “onshore”, but also, via section 12F(3)’s “extended geographical jurisdiction”, offshore, in countries which, like PNG and Nauru, have no local law.”

So why hasn’t the Government taken action on the injuries and harm that have occurred in a workplace that it funds and it manages? Perhaps it didn’t know of these incidents. Not possible as the Department of Immigration and Border Patrol (DIBP) representatives have discussed the issues in Senate hearings. Costello’s work was mentioned in the February 20 2016, edition of The Saturday Paper (available to subscribers only):

“Asked about asylum-seeker wellbeing while attending another senate committee on July 20, 2015, [DIBP head Michael Pezzullo] told Senator Kim Carr that the “government of Nauru is ultimately responsible” for the duty of care towards the detainees. “It’s a matter for the government of Nauru, yes.”

Fortunately, former WorkSafe Victoria prosecuting solicitor Max Costello heard that exchange and has dug out other material to unmask the figment.

Pezz’s answer was not on all fours with his own department, which three weeks earlier had advised that under the Work Health and Safety Act the Commonwealth is legally responsible for the care of asylum seekers.

In answer to previous questions on notice, the department told Carr that the WHS Act applied to the Commonwealth and under the legislation it is not permissible to either transfer or “contract out” statutory duties of care.

Further, the department helpfully conceded that the act has “extraterritorial application overseas”.

In other words, contrary to the answer Pezz dispensed to the senate, the statutory duty to ensure the health and safety of asylum seekers cannot be transferred to another government, to Broadspectrum, International Health and Medical Services, or anyone else.”

According to Fairfax newspapers, on June 5 2016, Comcare (Comcare regulates and insures federal agencies and departments) and DIBP documents

“…show that of 1092 injuries, and assaults reported to Comcare by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and its contractors over two years, almost 850 went uninvestigated.

Comcare is required to investigate so-called “notifiable incidents” and to put in place measures to improve safety based on those investigations. But the ALA claims Comcare takes a narrow view of the sort of incidents it should investigate in detention centres.

A Comcare spokesman said the Department of Immigration and Border Protection was only required to notify the authority about “deaths, serious injury or dangerous incidents”, and that sexual assault may not be seen as serious enough to warrant a Comcare investigation.

“Incidents of self-harm and sexual assault, for example, may not satisfy the definition of a notifiable incident,” the spokesman said.”

Notification to Comcare is surely a tacit admission that the WHS Act applies to RPCs.

On June 7 2016, The Age newspaper reported:

“The Australian Lawyers Alliance says the death of 24-year-old Iranian detainee Hamid Khazaei came after basic failures by departmental bureaucrats to uphold federal health and safety laws and they could be held personally responsible by the courts, even if their department is cleared.” (link added)

In his open letter, Max Costello counters the argument that the responsibility for each of the RPCs sits with each of the respective countries by pointing out to the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, Peter Dutton that:

“… with no apt local law, transferring/outsourcing of Act duties being unlawful, and your Department naming itself in charge at RPCs, PNG and Nauru cannot be legally responsible for asylum seeker health and safety.”

Costello addresses Michaelia Cash and Peter Dutton directly:

“… you both looked the other way while a government entity – the Department now shamelessly overseen by you, Peter Dutton – became an apparent serial offender against a workplace law, and remains unpenalised.”

Costello is likely to be able to do little more than try to shame the Ministers in action over possible OHS/WHS breaches as Ministers of the Crown are, according to lawyer Michael Tooma in 2010:

“expressly excluded from the definition of officers for a public sector organisation.”

Costello’s arguments are weakest when addressing the Prime Minister, but by criticising Malcolm Turnbull it reminded this author of some comments by the Opposition (Labor) Leader, Bill Shorten, on the ABC Four Corners program on 27 June 2016 (at the 50.26-minute mark) when asked about the self-immolation of detainees in the Nauru RPC:

“I’ve worked on workplace health and safety all my whole life. I’ve seen all manner of very bad outcomes for people in terms of workplaces. If I’m the Prime Minister of Australia, in all conscience, I can’t advocate a policy, that some of the Left would like me to, which would see people being sold tickets on unsafe boats and drowning at sea. But what I won’t do is, like the Liberals, because we want to deter people smugglers that what’s emerged is semi and definite detention so acceptable.”

Shorten mentioned his WHS experience without solicitation with the intent of showing that he is familiar with trauma, but he applied workplace laws to a non-workplace context. His familiarity with WHS issues should put him in a strong position to respond to the concerns and arguments raised by Max Costello and others should he become Prime Minister after this weekend’s election. Shorten may choose to address the issue of asylum seekers through the complex human rights process, but he could attend to the breaches of safety law and the lack of duty of care shown to detainees through domestic OHS/WHS processes in his first day in the big chair.

Inaction on these OHS/WHS responsibilities by both Bill Shorten or Malcolm Turnbull risks losing control of the debate. Victorian OHS laws allow a member of the public to seek a written reason for why an OHS Prosecution has not been brought. This opportunity is not in the Commonwealth WHS Act. Also, this weekend’s Federal election may provide more influence to the Australian Greens, which have been strong advocates for asylum seeker rights and have:

“… a policy of closing down the detention camps on Manus Island and Nauru and holding people in community detention on the mainland while their claims for protection are assessed in Australia.”

The Australian Greens have been supporters of previous Parliamentary inquiries into

“an examination of the impact, effectiveness and cost of mandatory detention and the alternatives”.

Following the recent release of its report into the safety issues at Manus Island and Nauru, the Australian Lawyers Alliance has made specific recommendations to the government about addressing the risks. These include

- “an independent judicial inquiry or a Royal Commission.”

- a review of the Commonwealth WHS Act, and

- “Comcare should review its interpretation of the WHS Act”.

The OHS profession has been almost silent on the consequences of the inaction by Comcare and the alleged breaches of workplace safety law. OHS laws have always been broadly applied. In fact, it is this absolute application that has been one of its strengths. The Government seems to be applying a selective application of OHS laws to an admittedly difficult situation but one that involves rape, abuse and the deaths of people in a workplace under the Government’s duty of care. This is unacceptable and must be addressed.

It’s a concern that Comcare have investigated so few cases. In a sense by not investigating or prosecuting, it has contributed to the harm because without any accountability or consequences for the PCBU, there’s been no motivation to change the policies and practices that have led to the harming of so many people, including a number of deaths. I’m a refugee advocate who has started reporting incidents to Comcare as I also have a Diploma in WHS and it is an area which is of interest to me.

I would love to discuss this more with Max Costello

Margaret, it should not be hard to make contact with Max. Here is a link to a profile of him – https://independentaustralia.net/profile-on/max-costello,473

There has been a lot of focus and significant claims made that Australia run the centre’s in question and that it has ‘effective control’. This is legal context; it is a legal term. The Australian government is very clear that they do not have ‘effective control’: They state that they do not run these centres. The government sates that it does not set the legal framework, nor own the buildings, nor employ the staff. The government also states that it does not set the policy framework, and don’t outline the labour laws under which people are employed. To this extent, the government has no control over the occupational health and safety legislation over those nations.

The consistent position taken by Australia is that while Australia is assisting PNG and Nauru in the management of the centres, this assistance does not constitute the level of control required under international law to engage Australia’s international human rights obligations extra-territorially in relation to the persons concerned.

In any legal argument there are always two points of view.

A very tasty bit of reporting (and analysis) KJ. Bravo.

Kevin: Max Costello here (the ex-WorkSafe prosecutor referred to in your blog). Well done to draw some threads together in highlighting and analysing the apparent failures by the Department of immigration and Border Protection to implement, and Comcare to enforce, the duty imposed on PCBUs (workplace operators) by section 19(2) of the WHS Act (Cth). That duty, as your readers well know, is to “ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the health and safety of other persons is not put at risk from work carried out … [at the workplace]”. As you note, non-compliance with that duty appears to be most starkly evident at the Nauru and Manus Island centres.

I did pick up one slip error. You say “Victorian OHS laws allow a member of the public to seek a written reason for why an OHS Prosecution has not been brought. This opportunity is not in the Commonwealth WHS Act”. In fact, the OHS Act provision you refer to, section 131, has been virtually cut and pasted into the WHS Act (Cth), as section 231. Like 131, it allows a person to write to the regulator requesting that a prosecution be brought if there’s been no prosecution within 6 months of an apparent offence. Reasons must be supplied, if, down the track, the regulator decides not to prosecute. I have invoked section 231 by writing two ‘please prosecute’ letters to Comcare.

Max thank you for the correction. I tried to find your contact details to speak with you prior to my article but without luck. Please email me at jonesk@safetyatwork.biz so that we may catch up.

Kevin

I agree that we have been silent on this matter, and it needs to change. WHS has been founded on ethical considerations, and should not be constrained by political discourse.