The Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) for Victoria’s draft Psychological Health Regulation does not seem to define what is meant by a psychosocial incident. (If I have missed it, please include a reference in the comments section below) In trying to establish a workplace mental health demographic, the RIS states that:

“As there is currently no legislative reporting requirements for psychosocial incidents, voluntary calls received by WorkSafe’s advisory service have been used as a proxy to estimate the prevalence of psychosocial incidents in the workplace.”

page 34

It is a pretty fluffy determination that the RIS accepts, further illustrating the need for additional data. The advisory service figures record 80% of psychosocial calls relate to bullying.

These Victorian reporting requirements are not intended to be the same as notifiable incidents. Notifiable incidents are clearly defined in existing OHS legislation and regulations. A psychosocial incident does not seem to be defined in the Proposed Regulations, but there is something called a “reportable psychosocial complaint”, which is

“… a complaint involving any of the following psychosocial hazards—

page 3

(a) aggression or violence;

(b) bullying;

(c) sexual harassment;”

Curiously the phrase “reportable psychosocial complaint” is not used in the Regulatory Impact Statement.

The New South Wales Code of Practice for managing psychosocial hazards at work also fails to define a “psychological incident” or a “psychosocial injury” or combination of these terms. Still, it does include these incidents and injuries as notifiable under the Work Health and Safety legislation:

“Where there is a notifiable workplace incident; such as a person’s death or serious physical or psychological injury or illness requiring immediate treatment as an in-patient in a hospital, the PCBU must ensure that the regulator is notified immediately after becoming aware of the incident and that a record is kept of each incident.”

page 25

WorkSafe Queensland offers this clarification:

“A work-related psychological or psychiatric injury is a disorder or illness that affects your mood, feelings, thoughts or behaviour that has resulted from your job. These types of conditions can include depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and more, and can be caused by a single event or develop over time.

Examples of things that can contribute to these conditions may include:

– a single event such as an armed robbery

– workplace bullying and/or harassment

– unreasonable action taken by management”

It is hard to see employers reporting bullying or harassment incidents to the OHS regulator if they are not doing so already, even if it is a regulatory requirement to do so. Bullying reporting figures have been overstated in the past, and the need to diagnose mental health conditions rather than rely on self-assessment has been discussed. There continues to be a lack of clarity on the definition of “mental health conditions“.

Psychological Hazard

The draft regulations do define a “psychological hazard” with examples. A hazard is different from the manifestation of that hazard which is likely to result in an injury. Still, it is reasonable to infer a potential incident from the definition of the hazard.

“psychosocial hazard means any factor or factors in—

(a) the work design; or

(b) the systems of work; or

(c) the management of work; or

(d) the carrying out of the work; or

(e) personal or work-related interactions;

that may arise in the working environment and may cause an employee to experience one or more negative psychological responses that create a risk to their health and safety;”

I would translate these to

- How work has been designed,

- The systems,

- The management,

- The work, and

- Relationships and communication.

To achieve a psychologically safe and healthy work environment, it is hard to avoid having a complete psychological audit of one’s business, as every element of a company is covered by the lists above.

In that case, it would seem a boon to the use of the International Standard for Psychologically Healthy workplaces – ISO45003 – in conjunction with 45001 that would cover all of the listed items. Still, it could also generate substantial disruption for any company that is not already at the stage of corporate maturity which can accept the necessary changes.

The Regulations may differentiate on company size, but size is not really the determining factor for implementing changes in psychological health. The OHS profession and regulators prioritised physical injuries over psychological injuries for decades for many legitimate and not-so-legitimate reasons, so reflecting this strategy in business reality is understandable.

The Regulations provide examples of psychological hazards:

- “Bullying,

- sexual harassment,

- aggression or violence,

- exposure to traumatic events or content,

- high job demands,

- low job demands,

- low job control,

- poor support,

- poor organisational justice,

- low role clarity,

- poor environmental conditions,

- remote or isolated work,

- poor organisational change management,

- low recognition and reward,

- poor workplace relationships”

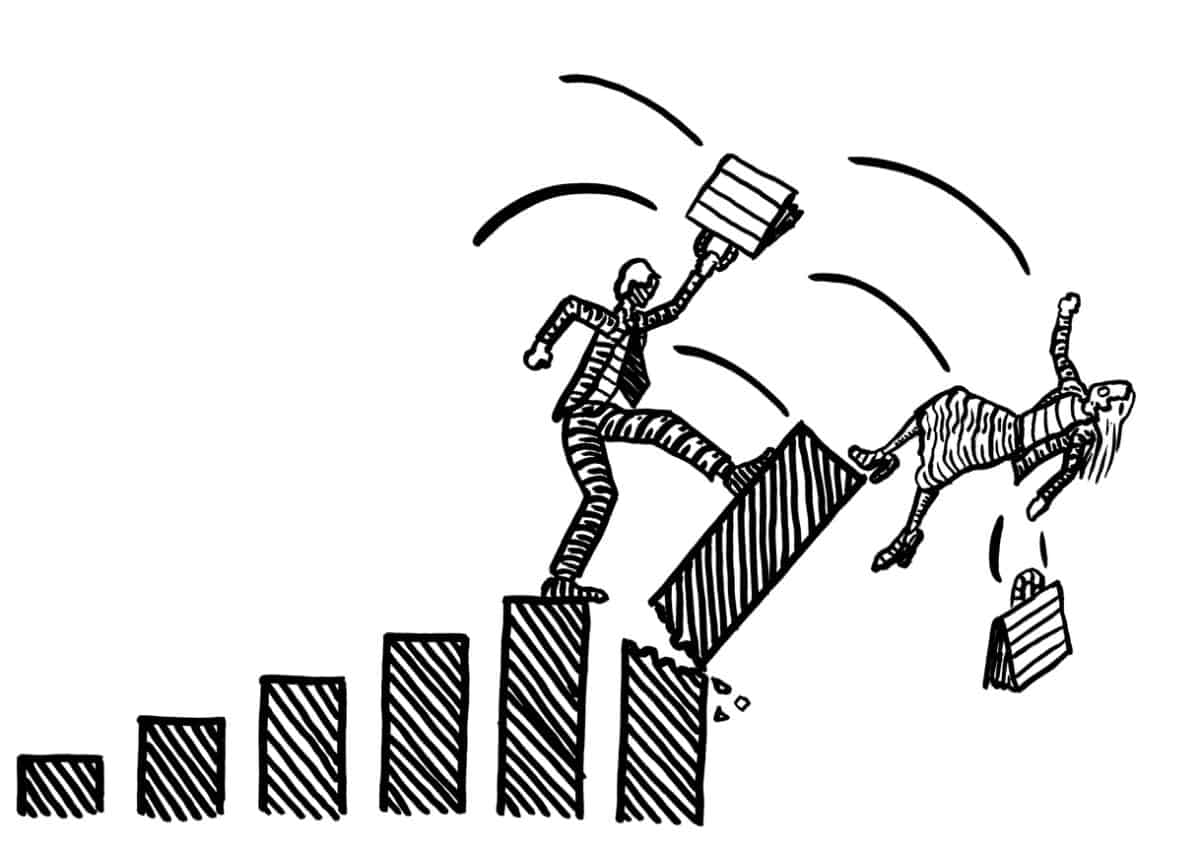

These hazards have been written about and discussed for over a decade with very little take-up by employers. Any one of these hazards could create challenges for companies with more than 20 or 50 employees. Many of these will require considerable involvement of the Human Resources (HR) professionals as these hazards have often sat in the HR patch. WorkSafe will need significant work to upskill HR to address these psychological hazards in a new OHS context.

Workplace Suicide

There is one type of unavoidable incident in workplaces – a death or a fatality. These are the worst-case scenario for any workplace but are also usually the easiest to investigate or study as there is little dispute that the death was work-related.

Workplace suicide is the psychological equivalent of physical workplace death, but there is always uncertainty about the role of work in a suicide, even when a suicide may occur in a workplace. There is even more uncertainty about work-related suicides. A suicide may occur anywhere, but the person’s mental state leading to suicide remains unclear without a note explaining the reason. Some people leave notes or a letter that clearly shows a link with work, but the work context is often inferred by discussions with close friends and relatives about the person’s mental state leading up to death.

This situation makes it almost impossible to be definitive about the worst-case scenario of psychological risks, but we can still work with estimates. The trick is to cut through the stigma surrounding suicides to achieve as good an estimate as possible.

The Regulatory Impact Statement includes only one mention of suicide – page 32 in a graph that shows no workers compensation claims for suicide. However, this graph is an odd inclusion in an analysis of Victorian OHS regulations as, it acknowledges, Victorian workers’ compensation statistics are excluded from the data of this graph. Why bother including a chart that excludes Victorian data in an analysis of Victorian Regulations??!!

Workers’ compensation claims for suicides are low for many reasons, but they do occur. The statistic is not zero.

Oddly, the RIS does not discuss workplace suicide because any analysis of physical injuries will surely include a discussion of deaths. Workplace deaths are a significant measurement of OHS performance. Government uses declines in fatality rates as evidence of successful strategies and initiatives but this will be unlikely in the context of psychological harm due to some of the reasons mentioned above.

If the government wants employers to report on work-related psychosocial incidents, as indicated by the proposed regulation, it needs to provide clear criteria for what needs to be reported. The Notifiable Incident criteria has been stable in Victoria and elsewhere for many years. This level of clarity is required for the psychological health regulations.

The big question is who determines and how is it decided that there is a risk to health and safety? Very often this lies in an individual’s perception and may have no relation to reality.

Richard, I think that uncertainty has been part of the reason for the regulations and for employers’ reluctance to engage with the prevention of harm. It has been convenient for employers to solve bullying, harassment and other psych problems by having HR performance manage workers out of the company when the OHS legislative intention was always for employers to be supportive of workers and be prepared to change the system of work to accommodate human variations.

I am hoping that the regulatory reform process will focus more attention on the diagnosis of mental illness in order to create a better evidence base but I am not confident.