[This article was submitted to The Age (and elsewhere) as a soft counter to so many workplace articles about health and safety that never include content from an occupational health and safety (OHS) specialist. It was never used, even though rewrites were requested.

So it gets used here and in support of this curious month of October where, in Australia, there are two separate monthly themes – Mental Health and Work Health and Safety. That these themes continue to be separate says heaps about the culture in each of these sectors]

Australian jurisdictions are amending their workplace health and safety (WHS) legislation to specify that the unavoidable duties and obligations of employers must now include the psychological health of their workers and not just physical health. These reasonable and long overdue moves are manifesting in new laws, and new guidances supported by new International Management Standards. The kicker in these changes is that, at least in Victoria, employers will no longer be able to rely solely on awareness training or resilience training to manage workplace mental health. This position could, and should, challenge traditional mental health trainers and lobbyists to recalibrate their workplace strategies.

For a long time, workplace mental health has been managed rather than prevented. The major mechanism for this is to update corporate occupational health and safety (OHS) policies to include the words psychological or mental health or wellbeing. From that stemmed training to reinforce these commitments. That training was intended to raise awareness of mental health in the workforce and often to provide workers with the skills to cope with workplace mental health risks, usually referred to as “resilience training”. These services were mostly organised through the Human Resources (HR) or People and Culture units. The OHS people were side-lined from this process and often let HR run with it because the legislative support for OHS intervention was seen as weak, and they did not have the skills to intervene.

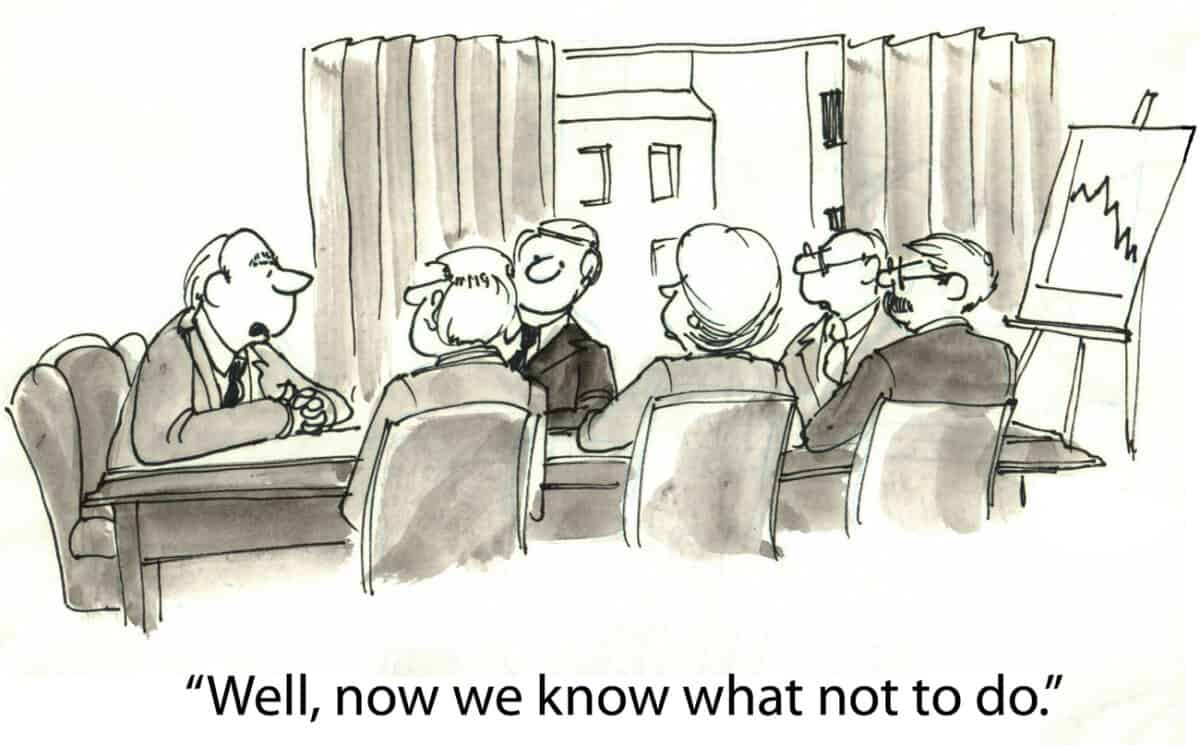

After all of this training over a decade or two, we are told that we are in as much of a workplace mental health crisis as ever. It is fair to say that the training option failed. Hence the increased attention to an alternative approach – upping the ante in OHS legislation. The challenge with this approach is that OHS/WHS laws require employers to prevent harm and not just manage it, so the various WorkSafes are pushing employers to look at their organisational and managerial processes to prevent and minimise psychological harm. Employers are to look into factors such as excessive working hours and the design of workloads to control job stress, travel times, rosters, leadership and supervisory skills. They are being encouraged to look at the existing HR data for clues or trends of stress-related absenteeism or workplace conflicts and dissatisfaction, things that can lead to workplace psychological injury.

No longer will employers be able to rely on the symptomatic relief coordinated through HR that manifests predominantly in yoga classes and fruit boxes, and other activities that provide symptomatic relief.

These changes are supported by research emerging from the Australian construction sector and elsewhere. Recently Professors Helen Lingard and Michelle Turner of RMIT university produced a suite of three research papers that recommend that no weekend work is scheduled so that workers have sufficient time to reconnect and strengthen the links with their families and friends. This change was seen as offering positive mental health benefits to workers with minimal productivity impacts. Overseas the Right-To-Disconnect for white-collar workers has a similar intention. At least one Victorian company freezes emails sent after the close of business on Friday and releases them on Monday morning to nudge workers to stop thinking about work and to reconnect to life.

These sorts of structural and operational changes are what the OHS Regulators are expecting employers to apply, and which will help employers comply with the OHS duties for psychologically healthy workplaces.

These legislative changes, or more accurately tweaks, are supported by various Codes of Practice and guidance, safety document types that the HR sector usually ignores. But there is also an International Management Standard for psychologically healthy workplaces (ISO45003), the development of which Australia has been closely involved. This strengthens OHS management systems in a way that can be audited and, if necessary, certified.

Although Victoria was the first State to amend its legislation, in some ways, New South Wales is more progressive. Its May 2021 Code of Practice for Managing Psychosocial Hazards at Work is highly regarded nationally and is likely to be a template for those States operating under the WHS laws. (Victoria continues to be out of step with its own OHS Act)

The legislative tweaks to emphasise employer obligations to provide and maintain psychologically healthy workplaces are political responses to the changing values and expectations of society, just as Industrial Manslaughter reflected society’s increasing intolerance of employers avoiding penalties and their lack of accountability. Workers expect to work without a risk to their psychological or physical health, and to become an Employer of Choice now, companies must look at how their businesses work and whether the way they manage creates or exacerbates psychological harm. A box of bananas, massages at the workstation and online mindfulness sessions will not be enough. The reality is that they never were.